Deutsche Bank Collection – Time Present

TIME PRESENT: A captivating time capsule-style exhibit unpacks photography’s development

By June Chua

It seems fitting that I finished the third and last season of the German Netflix sci-fi series Dark and soon after, visited the “Time Present” photo exhibit offered by the Deutsche Bank Collection at the PalaisPopulaire, on Unter den Linden close to Berlin’s Museum Insel area, on show until February 8, 2021.

I’m not giving anything away if I say that Dark’s premise circles on time, perspective and fate and it’s quite a ride. In many ways those themes dovetail with the exhibition—a journey through 40 years of photographic methodology sliced into chapters: Time Exposed, Today is the Past, A Moment of Intense Concentration and My Future Is Not a Dream. These could have been titles of episodes in the series. The thread of the exposition, which is not chronological, is how artists have dealt with time in their images since the 1970s utilizing different techniques.

I am highlighting just a few works here, it would be too difficult include and describe all of them—encompassing works by prominent artists such as Shirin Aliabadi, Kader Attia, Candida Höfer, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Gerhard Richter, and Amalia Ulman.

The exhibit (covering two mid-sized rooms) has materialized at the perfect time, coinciding with the rewiring of our existential clocks as a result of COVID-19. This compact and wonderful exhibit of 70 pieces provides a satisfying and fascinating interface for all the soul-searching you might need. By the way, I recommend downloading the PalaisPopulaire app. While you’re inside, you can access descriptions and voice recordings of the photographers explaining their work. The summaries are well done and the app is easy to use (for German speakers, there is a chat bot called MIA who can answer your questions about the photographs as well as any political, historical and cultural contexts surrounding the work).

In reference to spending our days staring at screens, I single out Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Rosecrans Drive-In, Paramount (1993) located in the Time Exposed section. It’s a stark white drive-in screen bracketed by palm trees in the dark. It could be almost anywhere. It is beaming out at you. You feel the expanse of an emptiness—we are staring into the void that we have created. Apparently, Sugimoto has recorded an entire film in a single exposure! What remains is a resonant white. This image spoke to me about our current existence—all of our experiences of silence, solitude and spiritual struggle are encapsulated in this pulsating screen of light.

So, I return to the beginning where I enter the first room of photos. Immediately, I’m confronted with a colorful, crowded but well-placed shot of Singapur Börse I (1997) by Andreas Gursky (1997). I’ve entered A Moment of Intense Concentration. It’s the perfect start as the picture jolts you and thrusts you right in the action. So many minute interactions are taking place, it gets your blood running. It’s one of the few crowd shots in the exhibition and this works with the journey one takes physically through the exhibition—our gaze is guided from an external human-created world to a more metaphysical plane as we glide through.

Soon, my senses are focused as I swing around to Zohra Bensemra’s in Afghanistan (2009) and Kenya (2008). Working as a press photographer and being one of the rare female Algerian photographers, Bensemra captures gripping in-the-moment images. In Kenya, a young woman in a deep purple shirt is shot chest up against a blue sky. She has a piece of paper and pen in one hand while gesturing with the other half-opened hand, her face and mouth appear to be either singing or saying something large and important. She is commanding the space. In the other one, a group of boys in Afghan robes and caps are staring intently upwards, their hands reaching up seemingly ready to catch something. Consequently, we are caught in the middle of a narrative of daily life somewhere else and it’s exhilarating. There is a mysterious intent reverberating from these images.

Remembrance and memory

Going forth, the section moves into a subdued mood as human beings disappear. I encounter Axel Hütte’s Vescona II (1991) and Wim Wenders’ Street Front in Butte, Montana (2000). Hütte’s is a breathtaking vista of gentle hills with distant stone dwellings framed by a square stone archway. We sense the abandonment and beauty. Meanwhile, Wenders gives us a cinematic, horizontal view of red brick storefronts (one has the telling signage of ‘connections’). Spare, clean, empty – this is a human construct without humans and we get the feeling he’s passing through and it’s this glimpse that is frozen in memory. The picture is reminiscent of small towns in America where there is no bustle, no hustle—moments like this aren’t hurried or fuzzy but clear and concise.

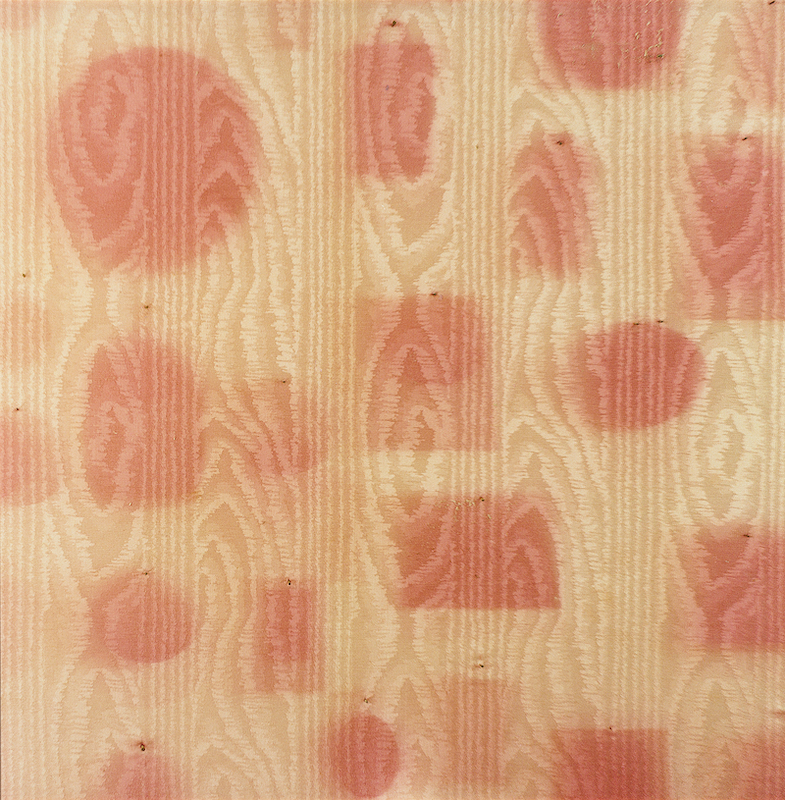

Rounding back to the other side of the room, I’m in Today is the Past. Yto Barrada’s Arbre généaloqique, 2005 sums up the section—a closeup of a wooden wall, small shadowy squares and circles mark where pictures had been hung. These ancestral ghosts of photographic memory are forever stained into the wall. It forces the viewer to consider how does one remember and commemorate? And, more vitally, it speaks to the idea of erasure and whether we can still recapture that history. How fleeting are our memories and images anyway? This is answered by Mohamed Camara’s Le foot pour moi, c’est dans l’eau (2012). Camara gets people to choose a younger photo of themselves, holding a clear bag of water where the image is superimposed. In this one, we see a photo of a black man in soccer gear. Indeed, memory and the past are like water, you are unable to properly retain them.

What does it mean to plan and dream?

I head to the second room downstairs and that’s where I encountered Sugimoto’s drive-in movie screen which is keeping company with Sigmar Polke’s two Uran (1996) shots: one is purple and the other is green. To describe them so simply is to do an injustice. Polke’s colors are luminous, warm yet cold, and when the eye meets them, it is bathed in a kind of energy field. The pair are so alluring, you can’t help but soak in their radiance. After months of being cloistered and watching too much online TV, I feel cleansed.

As I enter the final section, My Future Is Not a Dream, humans re-appear more as portraiture. I must mention Dark again—as I ponder COVID times and the reality and surreal-ity of what it means to plan, hope and dream now. This is why Cao Fei’s set of shots in a Chinese lightbulb factory are so striking. Young individuals are placed in the factory setting (mostly empty) and doing something they must have dreamed of. I like the young man holding an electric guitar, My Future Is Not a Dream 04 (2006). He’s dressed normally, a worker is blurred in the forefront. One can wonder about the future of this young person in a world driven by consumerism and a capitalistic ethic. The other picture had a young woman dressed in costume and posing as a dancer. How many of us toil in real and imagined factories, our dreams denied or delayed?

The final shots speak to current status of the world. I recall Kader Attia’s Man in Front of the Sea (2009). We see the back of a man in jeans and a shirt, atop a jumble of massive square concrete blocks staring towards a sea horizon, what must be ships in the distance. Spare and evocative. I am, metaphysically, also there with him.

Lastly, I enjoyed Miwa Yanagi’s pieces. My Grandmothers (Sachiko) from 2000. It feels ever so now, in present. An elegant, older Japanese woman is in an airplane, staring out of the window, her half-eaten airplane meal before her as she gazes into the light. She looks wealthy and weary. Yanagi spoke with young women and asked how they envisioned their lives 50 years hence. She coordinates a scene based on these chats and ages the young women living out their imagined future.

Most of us are, at the moment, unable to travel or perhaps, are scared to due to COVID. This photo is like a remembrance of what was and could be and yet, it is so very solitary. The woman is jetting somewhere presumably to find connection and experience. In this time, what we have is just ourselves and the world within—an imagined future out of grasp.

A text from Sachiko accompanies this piece and it chillingly foretells of 2020. Here are its opening lines:

Even though I thought I had become totally used to living alone by now,

yesterday, no matter how hard I tried, I just could not stand being in the house by myself.

It seemed as if the winter sunset had overtaken the entire world.

and was, little by little, scorching everything in its path.

[…]

Review by June Chua, August 2020

© all images by the artists / Exhibition: Deutsche Bank Collection „Time Present“ – Photography from the Deutsche Bank Collection, PalaisPopulaire, until February 8, 2021 www.db-palaispopulaire.de