Julien Lescoeur

I have a deep interest in composition and cadrage. Verticals, horizontals and volumes matter to me. And then there is always a source of light in my photos — be it a window or a neon lamp. I tend to take frontal shots of my motifs. As a result they seem to be even more isolated from their surroundings. And as a result of all this, these photos almost become fictional. They are cut off from their surroundings, they stand for themselves, they hold secrets and you can start to imagine your own fiction or narration while gazing at them.

Julien Lescoeur

Max Dax: Julien Lescoeur, you tend to work intensely on every new photographic project, usually for months or even a year. Do you freeze time with your stills?

Julien Lescoeur: I am working with a large-format camera. I have to carefully consider what and how I want a photo to be and how I will determine the cadrage. Every shot costs me money. So I definitely consider many aspects before I press the shutter release. I go through many different camera angles to really understand the composition that I am looking for. This especially applies to my series “Interzone”, which I started working on some ten years ago. But some of the “Interzone” photos are as recent as from last summer, while earlier motifs date back to 2007 or even 2006. But even if I allow myself to have time breaks in between, the new photos still contribute to and belong to the same narration. New photos can be added to an existing string of motifs when the time comes as each photo inherits elements of the next one — even if there is a time gap of a year or even longer in between.

MD: The “Interzone” photos focus on indoor motifs such as concrete stairs or spaces that look like subterranean parking lots or empty corridors. They are all done in the same fashion and they all feature concrete walls and floors and stairs. As a result, they are concrete spaces.

JL: These are spaces that you find in big cities. These are anonymous spaces where you can easily feel isolated. I like to call these spaces “in-betweens”. You can’t really figure out where exactly the space is and you lose the connection to time. This actually applies to all of my works. But these leitmotifs seem to be very coherent in the “Interzone” series. You begin to lose yourself in time. I did also photos of barriers. You can see through glass windows or through bars, but you can’t enter. What you are looking at is closed and sort of off-limits, you are only allowed to look at it. So, yes, this question of time is actually very present in my work.

MD: By taking away the context, you isolate your motifs?

JL: Yes, absolutely. And this applies to all my photos — be they pictures of gas stations or parking lots at night or detail views of concrete staircases. When I go out into the public space of a big city, I am seeking ghosts and isolation. Only afterwards a long process of re-appropriation starts, which absorbs all this information and extracts it into compositions.

MD: The framing of your photos is often very symmetrical. Are you looking for invisible grids — like in Mondrian paintings?

JL: I have a deep interest in composition and cadrage. Verticals, horizontals and volumes matter to me. And then there is always a source of light in my photos — be it a window or a neon lamp. I tend to take frontal shots of my motifs. As a result they seem to be even more isolated from their surroundings. And as a result of all this, these photos almost become fictional. They are cut off from their surroundings, they stand for themselves, they hold secrets and you can start to imagine your own fiction or narration while gazing at them.

MD: “Interzone” is only one of many series that you are working on in parallel. Is there a connection between the series?

JL: Every series exists for itself, but the connection is obviously the aesthetics and also the topics. The best example for this is my “Aerolitiques” series. It stands for itself, but it is a direct resumption from working intensely on other series in the past. In hindsight it feels like certain series had to be done in order to bring myself into the position that I can materialize or intensify certain aspects of my previous work in a new series.

MD: “Aerolithiques” is a series of photographs that has close ties to “Interzone”. But the five photos that are exhibited at Santa Lucia Galerie in Berlin go a step further.

JL: That’s true, it is essentially an extension or an upgrade of a previous series. I tend to heavily refer to my own work. As a young artist I also have to be aware of the fact that I am building up my own body of work — a catalogue raisonné. Therefore I ask myself: What do I really want to express? And, more importantly: What’s lying ‘behind’ the photos?

MD: In terms of: What is behind this box?

JL: Yes. What lies behind a surface? It’s something that you cannot see. You can only see the surface.

MD: The greenish-blue atmosphere of the preceding “Interzone” photos has faded into an almost monochrome grey scale. Oddly enough, the “Aerolithiques” look like they were painted, even if you view them at close range.

JL: There is a very strong influence of painting inherent, the idea of drawing, of composition and of color. So, for me it is a natural thing when my photography starts to look as if it was painted.

MD: Do you feel like a painter then?

JL: No, I consider myself as a photographer. But I spend much more time looking at paintings than at photographs. As a photographer you can transport information like a photo journalist does. Or you can be a fashion photographer. Or a portrait photographer. But when you work in the field of art then there are no rules. You have to find your own subject and to define your own rules. You create your own topic and your own style. And you have to be very strict with your growing body of work.

MD: What are your rules?

JL: Good question. I don’t know. I actually feel very free.

MD: But each of your series seems to follow different rules.

JL: If you study the chronology of my work — and Lucia Margarita Bauer was the only person who really understood this from the beginning — you will notice that my first series were entirely shot in deep darkness. They therefore have an inherent tension and they contain inwardly bound violence. But after that I did another series called “Interstices”. All the photos were shot during the day in a private place, my apartment at the time. By chance I had been offered an apartment in a plattenbau in Linienstraße, Berlin. I started to realize that this space was a great subject for photography. There were public rooms within that old but somehow modern building that had brand-new furniture. That was a stark contrast. There was something wrong; the two elements didn’t match. It was a plattenbau, remember? The ceilings were very low. Certain furniture within these narrow rooms or corridors destroyed the proportions. There was a notion of trepidation within the building, as if there was no escape. That’s why I show no windows in these photographs. If you see the frontal view of the opposite building, then the photo was taken from the window, but you can’t see the window frame. I had to think of Cabaret Voltaire’s song “No Escape” when I worked on this series.

MD: Since it was your apartment and you lived in that building — is there a diaristic aspect to this series?

JL: I guess so. I mean, this is my life, isn’t it? I have tried to capture a tension that I felt when I did my nocturnal photographs of gas stations and I tried to freeze a notion of anxiety within the apartment, an anxiety that I’d describe with the feeling of having no escape. And then, in yet another series which is called “Escales”, I’m looking for the light. That’s my series of staircases. All of the photographs I shot for that series have the same angle: They always tend towards the light, upwards. There is an element of elevation in these photos. All of my series are coherent within themselves.

MD: All of your photos show aspects of urbanity. Why is it that you’ve never done photos in nature?

JL: The idea never occurred to me. It might happen one day. But until now I didn’t feel the necessity. I never felt like I was running out of motifs. I felt the spirit of creation with every series that I’ve worked on. I mean, put any two artists in a room and ask them to take a photo. You will get two completely different pictures. For me, every series is a construction, and if you compare the various series you will notice connections between them. There is definitely an evolution from one series to the next. I simply had to express my feelings of living in a large city. I wanted to materialize these feelings in my photography. Maybe, if I had lived on the countryside I’d been researching other motifs? Who knows?

MD: Have you always lived in large cities?

JL: Yes. I grew up in Paris and I’ve lived in Strasbourg and Berlin. I definitely think that there is a connection between the place you live and the art you make. Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat and Sonic Youth all lived in New York. Kraftwerk, Thomas Ruff and Andreas Gursky come from Dusseldorf. The environment has an influence on your creation. You re-interpret, one way or the other, your surroundings.

MD: What does the term “Aerolithiques” actually mean?

JL: It’s French and it literally means “out of space”. It describes something that you cannot identify, something that is from out of space. It took me a long time to actually find the title. It came to me three years after I had made the photos. My photos are not telling you what to think or how to interpret them. A title therefore must deal with that. The title shouldn’t be a “key” to interpretation. But of course it has more to do with the idea of space than with a scientific approach to space. The photos are encounters with objects that you can’t identify.

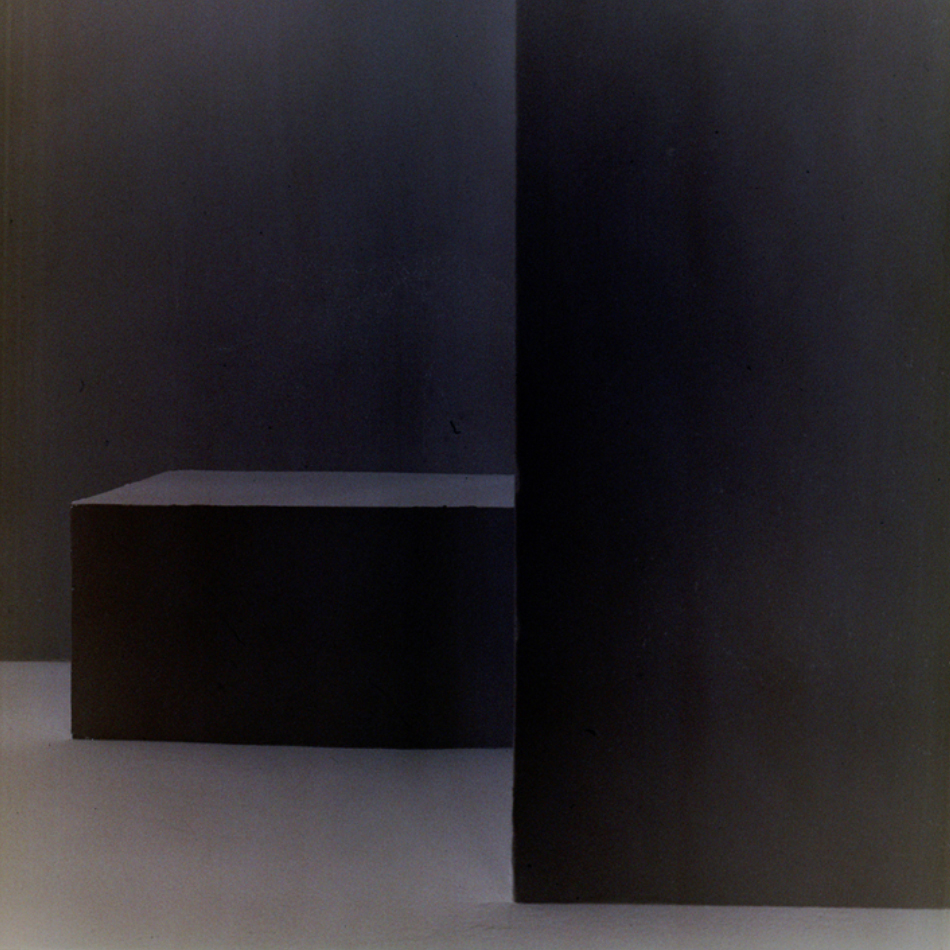

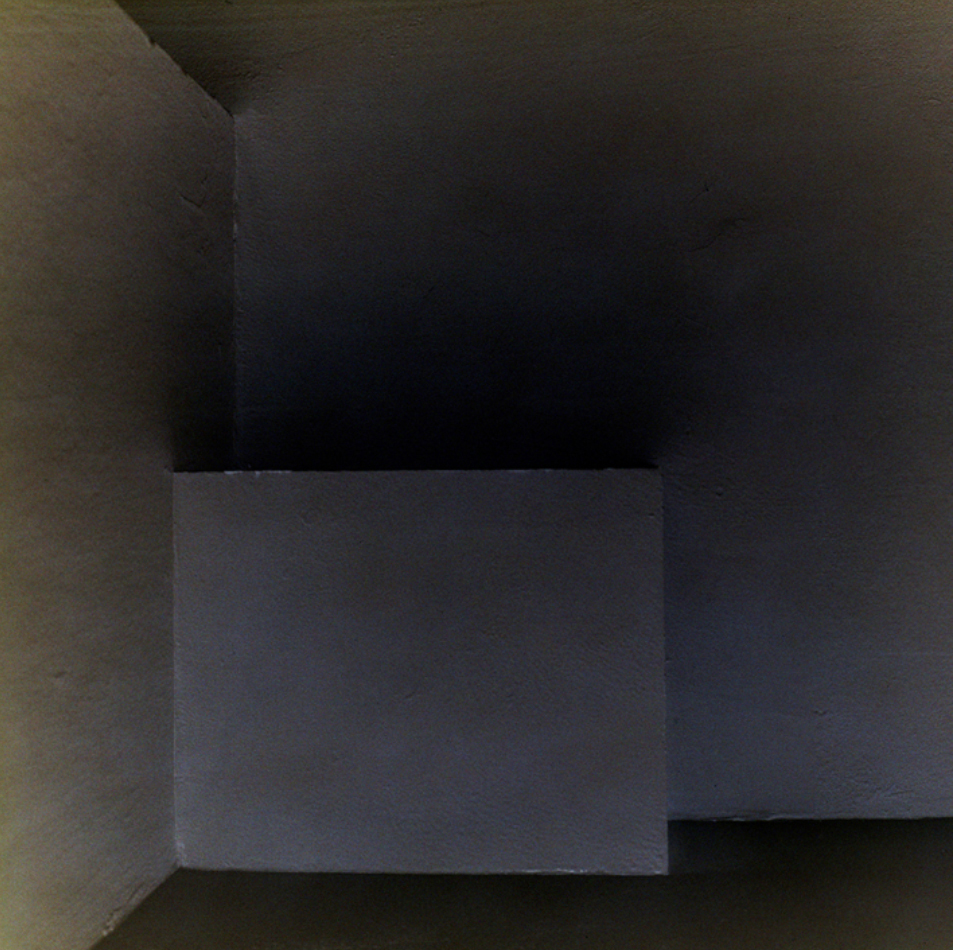

MD: The ‘Aerolithique’ seems to be nothing more than a grey, cubic box.

JL: Yes, but the cube is a symbol. It is charged with a broad scale of references — paintings, films, legends and the idea of isolation. The monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s “A Space Odyssee” stands for God, the creator of the world. In that sense, a simple cube can be loaded with significance and can therefore be a very strong object. I try to analyze the absolutism of the cube in my photographs. And I analyze it by using the simplest elements that photography allows: horizontals, verticals, volume. The resulting images are then subject to interpretation.

MD: What cube did you actually photograph?

JL: I had a studio during my residency at ZKU in Berlin-Moabit. On the ceiling some pipes were covered by a white, wooden box. Actually, the whole room was painted white and so was the box. I had this object just over my head all my day. I started to stare at it and I finally decided to make some photos of it.

MD: Was it an otherwise empty studio?

JL: No, it wasn’t empty. On the floor I had a sofa and some furniture. But the ceiling was empty — except for this box that was supposed to hide the pipes.

MD: You were looking at the ceiling and you saw a different space?

JL: Exactly. Every morning I’d have my coffee in my studio and gaze at the ceiling. And after some weeks I noticed the cubic wooden construction up there was clearly not a part of the original architecture. It had been added eventually. That struck my attention. In every of my previous series I reinterpreted something that I had seen in the urban environment. And this time I started to examine and to reinterpret a three-dimensional structure in my own studio.

MD: Do you try to abstract?

JL: That’s what I mean when I use the term “to isolate”. I isolate or abstract an object from its surroundings — be it a gas station at night in the moment where absolutely nothing is happening or be it a box underneath my studio ceiling. Getting a perfect frontal view of that box then becomes my subject for the next weeks or months. In this case I had to get a huge ladder to get really close to the box. Then I started experimenting with a tripod that I would glue to the ceiling. Some of the photographs from the “Aerolithiques” series were taken from a camera angle really close to the ceiling, only 20 or 30 centimeters away from the box — there simply wasn’t more space I could use. I basically did the photos upside down. And that’s exactly why you lose the perspective when you gaze at them. They are not only headfirst, but also inverted. It’s basically what you’d see when you’d look at the negatives. This way, the images become more open to interpretation. They become symbolic. You lose the aspect of architecture.

MD: The images from the “Aerolithiques” series have an eerie quality; they are very dark and haunting.

JL: This double inversion upside/down and negative/positive creates an atmosphere of fiction.

MD: Are there ghosts present in your photographs?

JL: Yes, there are. Before I made the “Aerolithiques” I had been having a break for a year. I hadn’t made any photos because a very dear and close person in my life had passed away. So, when I photographed the box on the ceiling there definitely was the ghost of that person present. I would go so far as to say that death is present in these photos. In that sense, the “Aerolithiques” are the most personal photos I’ve ever made in my life.

MD: Why did you stop doing your work for a whole year?

JL: It’s not that I didn’t do anything. I did exhibitions and I was thinking a lot. It’s all work in the end.

MD: Your photographs remind me of the films of David Lynch, the photographs of Gregory Crewdson and Edward Hopper’s paintings. Do you follow their path?

JL: My photographs are actually very different from Gregory Crewdson, but I would agree with David Lynch and Hopper. My photos are not staged. They are results of long processes of research — which is even more complicated and time-consuming than inventing a scenario. Furthermore, I don’t use flash and I don’t Photoshop any of my photos either. I only use my camera and natural light. And we shouldn’t forget Giorgio Morandi, who was an Italian painter who became famous for developing an almost monochrome tonal subtlety in his still lifes. My “Aerolithiques” series features equally minimalistic and simple forms with different specific depths and a grey scale of colors. The topic perfectly suits the approach of painting.

MD: What about music? Do you hear music when you work?

JL: I should mention Joy Division. They come from a working class city in the North of England and their music is haunting. In their music there is inherent violence, but it is contained. And that is also the point with my work. You can feel a violence that is about to explode, but it remains contained, like an inbound aggression. With my photographs I describe a world that is under tension.

MD: So your photographs basically show the moment just before the explosion?

JL: Very nicely said. I love Sonic Youth for that same reason. They make noise, but they do it very specifically and they hold back the outbreak. It’s the same with Jackson Pollock. There also seems to be a contained violence within his paintings. As opposed to, let’s say, a group like AC/DC that don’t contain their violence within their music — they let it straight out.

MD: Do you photograph all of your series with the same camera and lenses?

JL: I am mostly working with a 5” by 4” folding camera. But I also sometimes use a medium-format camera. I like to work with the large-format camera because it forces you to really figure out what photo you really want to shoot. There is no comparison to the speed when you work with a high-resolution digital camera for example. To work with a large-format camera sometimes takes hours or days or even a week. And then you may have shot two photos, or one, or not even a single one because you have to rethink the approach. I have no idea how a rich photographer would handle a similar situation. Maybe he would do more photos because money wouldn’t matter to him. But I doubt that the final results would be any better. The more I think about it, the more I come to the conclusion that investing time in thinking about the right angle, the right set-up and the right moment is imperative. It means focusing. In other words: I don’t produce so much. This also minimizes the expenses. Buying my films in Berlin instead of Paris also helps, as the market seems to be more competitive in Germany than in France. You get the same films for almost half the price in Berlin. One of the reasons why I frequently visit Berlin is that I can always refill my stock. The other reason is that I have friends in Berlin who I like to visit as often as I can.

MD: How patient do you have to be to work at such a slow pace?

JL: Ha, ha, ha. I guess I am a patient person. And I am fully aware that every photo I take could potentially contribute to my body of work. I started my catalogue raisonné ten years ago. And I haven’t produced a vast quantity of photos since then. If you work that way, patience is absolutely necessary. Every photographer will agree. And I wouldn’t be surprised if a painter would answer in the same manner. I know painters who work for months on a single painting.

MD: But you do shoot more photos than you present in your small printed catalogues, which seem to serve as registers.

JL: Yes, of course. For the “Interzone” series, for instance, I took a lot of photos within that huge concrete underground space, but only a few ended up in what I actually call ‘my portfolios’. I keep and archive these outtakes as they are also a potential quarry for future use. This is the process of creation.

MD: In other words: Every now and then you revisit your archive and re-evaluate it?

JL: Yes. It happened to me that after a couple of years I stumbled across some older photos, which I thought I could finally use. I have to do some of the photos to understand the architecture of the space. It was like research within research. I had to find a subject within that space. I need prints of my photos to understand the subject and to go further from there. All of this happens slowly. When I’m ready to work on a new series of photos, I always decide to spend six or eight weeks just doing that. I allow myself no distractions during that timeframe. I accept that this is a part of the process. Only if I have this timeframe secured can I approach my subject and thus my motifs with the necessary patience. It might seem paradoxical, but I basically know how a photo will look like before I shoot it. The research means that when I finally press the shutter release button on my camera, I know exactly how the photo will look. And this means that I have to patiently find the angle that leaves me 100% sure that the result will be exactly the way I want it. Then I print it and look at it and hopefully this process leads somewhere. So basically every photo I take is to a certain extent perfect — for me. But when I then decide which six or ten or twelve photographs I will use for a specific series will actually end up documented in a new portfolio, I also produce a small pile of leftovers. These leftovers might contain new directions for future projects. But while I am progressing with my different series and expanding my body of work, I might reach a point where I’d find a new subject within a section of my archive. And some of these photos then may become part of a new series. This has happened with the “Interzones” series: After some years I re-approached the original material and by zooming into some of the photos they became much more abstract — to the point of total, monochrome flatness. You definitely need to be patient in more ways than one if you want to build up such valid self-references within your body of work. But there are even more radical examples with my “Velvet Doom” series.

MD: “Velvet Doom” already sounds like an album or a song by Bohren and der Club of Gore…

JL: Ha, ha, ha. But it’s true.

MD: You should suggest to them using the photos for a forthcoming album. They are haunting — just like their titles.

JL: Talking about “Velvet Doom”, I first limited the series to just three photos. I put many other photos aside. A few years after I had made the three “Velvet Doom” pieces, I re-visited them and radically zoomed into them. By doing so I discovered interesting aspects in the photos and in their grain. I then extended the series with five more abstract, almost monochrome photos. In that sense I don’t always have to shoot new photos to start working on a new series. A new body of work can be also a re-interpretation of something old that seamlessly blends into something already existing. It basically complements it or takes it further. I am basically going deeper and deeper into the DNA of my photos. In a very literal way: By zooming into the pictures, the original motif eventually vanishes — like in Michelangelo Antonioni’s film “Blow-up”.

MD: How do you decide how many photos it takes to open a new chapter? What made you select only three, as in “Velvet Doom”?

JL: In the case of “Velvet Doom” I was able to say everything I wanted to say in three frames. But it generally helps to think in editions. An edition shouldn’t get out of hand. To make these decisions and to be forced to make a selection is — again — a part of the process. I believe that it is important to narrow down your body of work to its absolute essentials. But after a few years I reconsidered again the “Velvet Doom” series after having made the “Aerolithique” series, as there is this similarity of forms and aesthetics.

One day I realized that the “Aerolithique” series was somehow an extension of my experiments with “Velvet Doom”. It was a logical step to revisit the leftovers of the “Velvet Doom” series and to finally extended it to eight photos instead of three.

MD: You did your latest series in and for the Petit Palais in Paris. How does this series of indoor museum stills blend into your previous series?

JL: There are many connections. The only real difference to my previous series was that I was free under the condition that all the photos had to be shot within the premises of the Petit Palais museum. I’m not used to working like this. Usually I chose the place I want to picture all by myself. This time it had to be the Petit Palais, which was built in 1900 for the Paris World Fair.

MD: Did they give you the keys?

JL: Almost. I was allowed to shoot there on Mondays when the museum is closed for the public. I was alone in a museum in Paris and monitored only on CCTV. This idea to spend hours and hours and Mondays after Mondays alone in a museum turned out to be very tempting and I accepted the offer and the conditions. And for me it was clear from the beginning that photographing the architecture or the artworks wasn’t an option for me. So, in the spirit of my other series — and here’s the connection — I focused on the ghostlike presence of the museum. I started to get interested in the museum benches that had been installed for the visitors to sit down and gaze at the artworks. I started to like these empty benches. And then I noticed the white sculptures that were standing in various corners inside the museum. I realized: They were the real inhabitants of the building. They were like friendly ghosts. One of the statues even had a subtle smile on her face. She seems to say, “welcome”.

© all images by Julien Lescoeur