Christopher Taylor

Marks in Time

Steinholt is the third series of photographs that Christopher Taylor has dedicated to Iceland, the homeland of his wife, Álfheiður. The first series, From Under the Glacier (1996–1998), was entitled in honour of the book Kristnihald undir Jökli (1968) by Halldor Laxness, while the second was devoted to the Westman Islands (Vestmannaeyjar, 2006–2010) from where Álfheiður’s mother originates.

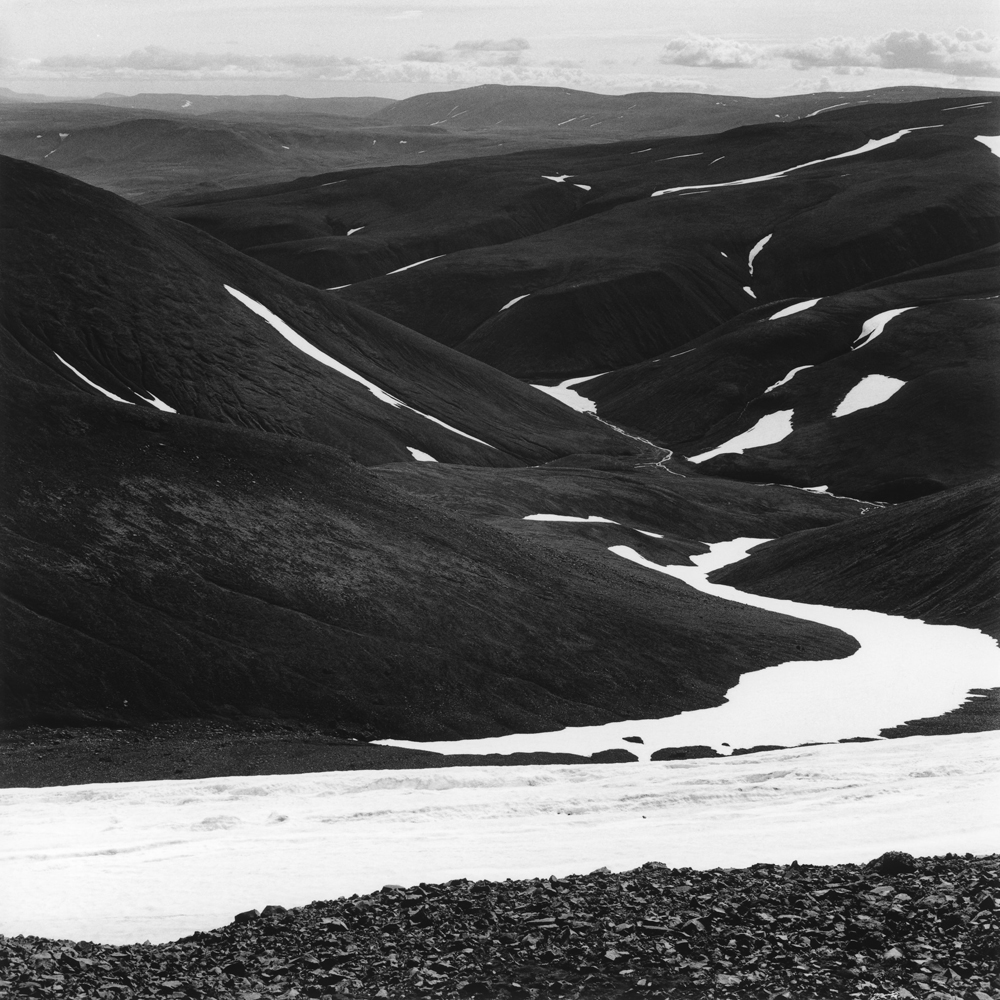

Christopher’s relationship with nature and human life in Iceland has deepened since he and Álfheiður acquired Steinholt, a modest house built by Álfheiður’s paternal grandparents in Þórshöfn, on the country’s north-eastern coast. Since then, Christopher returns each year to this tiny village, home to around 300 people. Here he has devoted himself to restoring the house, working for a fish freezing plant, and above all (weather permitting), exploring the local terrain in long, arduous hikes. No longer merely a transient guest, struck and fascinated by the indomitable grandeur of the natural environment or hostage to enclosed spaces during spells of bad weather, nowadays Christopher shares part of his life with the villagers of Þórshöfn. He makes the time he spends there meaningful by interpreting the surrounding landscape and observing the traces left behind by people who have perished or moved on, still remembered by those who remain.

The stories that Christopher has learnt, both through oral accounts and by drawing on the collective memories recorded in the 1940’s by local farmer and writer, Benjamin Sigvaldsson, have struck and moved him through their simplicity and harshness. They are the experiences of men and women whose main activity and preoccupation had been survival in a forbidding inhospitable setting. Raisers of a few scanty sheep, fishers when the sea allows it, in a country where the wind and cold mean that even trees show stunted growth; at times these people have been the heroic protagonists of almost intolerable situations. Often unable to make a living on the isolated farms where they were born, they would leave and start anew elsewhere. While some suffered abuse, others demonstrated courage and resolve under the most adverse circumstances; all painstakingly survived by gleaning what little they could from the surrounding environment.

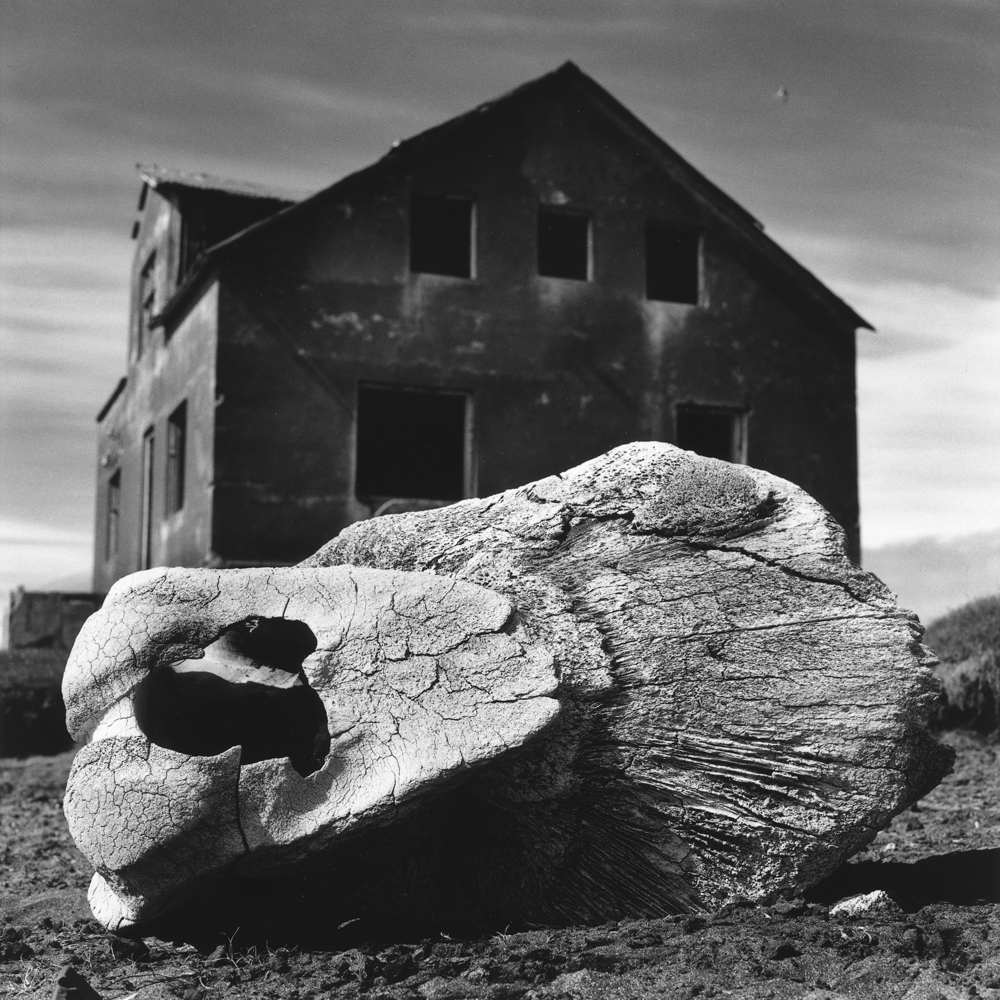

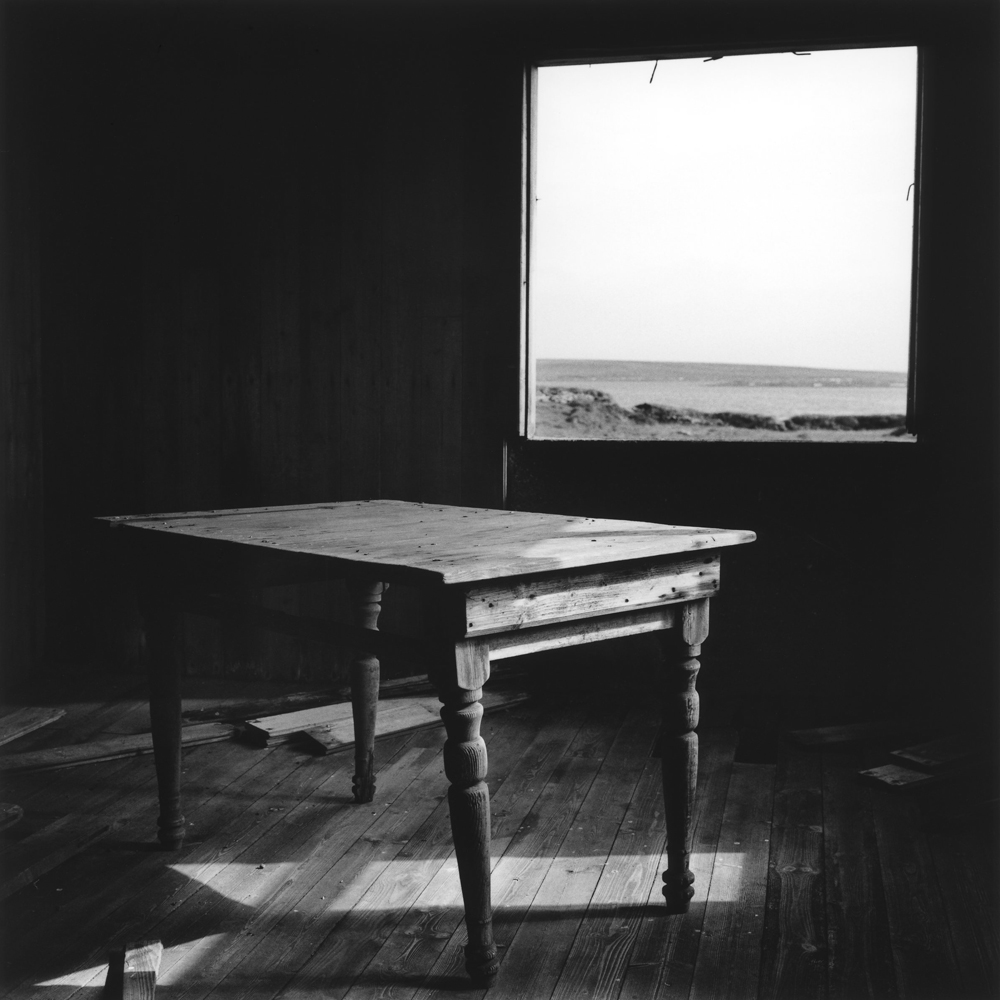

The series of photographs collected under the title of Steinholt — A Story of the Origin of Names, alludes to the fact that the names of elders are passed on to younger generations, so as to prolong their memory. The photographer has created his own personal fresco here, in some cases intending to recall details of the past, but which manages to go far beyond the sole evocation of bygone events. Even when they portray specific places and experiences, these images do not require any anecdotal explanation. The natural environment in these areas, so ill suited to sustaining human life, retains a beauty and purity that is difficult to find in more hospitable settings. Dwellings, be they ruins or recently abandoned, make up for meagre furnishings with breathtaking views from unhinged windows.

In the digital era of fast, distracted communication, Christopher continues to use old, heavy analogue cameras and black-and-white roll film that he personally develops and prints. The months spent steeped in this island’s landscape, exposed to the elements, are followed by long days in his darkroom in the South of France, where his time is consumed in sealing these memories on paper, sustained by endless cups of tea. The photographer’s Icelandic summers, swathed in limitless light, are thus followed by long periods of self-imposed “darkness.” It is through this rigorous regime that his images are distilled, delivered as hymns to beauty in which blacks and whites of endless shade lend a higher, more ethereal quality to these snapshots of life.

Landscape, architectural fragments, animals, and portraits—these are the themes of all three series devoted to Iceland, which collectively convey a rather full picture. In these open, natural spaces, the eye may wander towards distant or nearby elements, focusing on commonplace details (a brooding duck, or a few rhubarb leaves) rendered poetic and charged with significance, or to infinite horizons that are striking and sometimes frightening in all their primordial energy. Christopher loves the freedom to be able to disappear and not be found or even sought. This is a wish the Icelandic landscape easily fulfils. It is part of a method he uses to place himself under circumstances similar to those the inhabitants of this region encountered fifty or a hundred years ago, in an attempt to relive the experience.

Familiar Gazes

In contrast to photographs taken in China and India—the two countries he has most frequently visited besides Iceland—here the photographer’s personal life is involved. The photographs evoke Álfheiður’s family history and are infused with a quality of intimacy. Christopher delves into traces of the past within the surrounding environment in search of a key that may provide a greater insight into the woman who has been his partner for over thirty years. In Iceland, he is not just a well-informed, thorough traveller, but also a man who wants to be part of what he sees and find out what it means. The way in which he expresses this sense of belonging is nonetheless only suggested: the autobiographical details are emblematic, thus it is not essential if one of the crumbling farms is actually the one in which his wife’s ancestors lived because most Icelanders can recognise similar elements in the stories of their families.

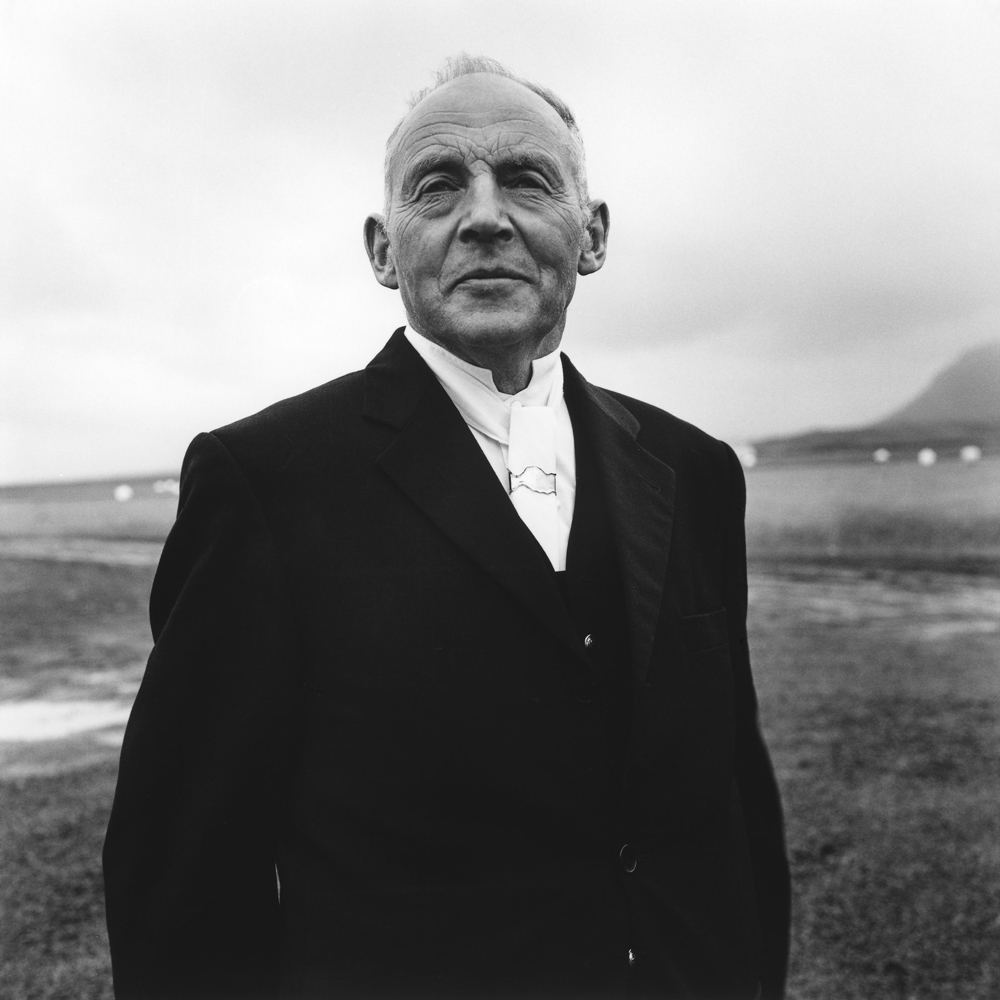

The portraits are of people who live in Þórshöfn or thereabouts, and have (or had) some sort of relationship with Álfheiður’s family or with the photographer himself who would run into them while going about his daily business, or on one of his hikes, and whom he recognized as personifying the very essence of the area’s inhabitants. They are men and women with whom Christopher spent hours or days, and with whom he shared meals and conversation, whom he observed in the hope of seizing both their similarities and difference. One could say that they were posing, in the sense that they knew they were being photographed, but their gazes show that they did not change for the benefit of the lens. They retain an inner “integrity” sustained by a feeling that they are in tune with the image of themselves that the photographer will convey—it is a sign of great trust. We tend to ask ourselves who these people are. We imagine anecdotes and blood ties that often do exist, but, as can be said for all of Christopher’s images, these portraits seem animated by a life of their own that nurtures us, through a mute, yet intense, gaze. Perhaps the only truly “contrived” portrait that merits a brief explanation is that of his wife holding a mirror that belonged to her grandmother, Álfheiður (whose name the two women share). In the photograph, the granddaughter’s face is curiously only mirrored in part, as if to suggest that she only partially recognizes herself in the figure of her beloved, esteemed grandmother, given that life has led her faraway, where she was able to find unimagined and unimaginable possibilities.

Lines and Spaces

Ever since, over ten years ago, I began following Christopher’s work, I noticed his penchant for central, solid compositions with a preferably square format and often structured along straight lines. This last feature is especially obvious when he photographs architecture, but a number of sharply delineated horizons in his numerous seascapes also come to mind. The images he envisions are almost always symmetrical and aim for a harmony that renders them perfectly balanced. He possesses a great, innate talent for calibrating the elements within a photograph, which means that overly “full” or dark spaces are counterpointed by more luminous, empty ones that are not necessarily the same size, but which precisely contribute what it takes to create a visually balanced image. Sometimes they are but flashes of isolated light, yet so powerful and significant as to counterpoint even extensive dark areas. Many photographs display a skilful, organic combination of straight and softly curved lines, and it seems to me that Christopher’s eye does not mean to distinguish between what is “artificial,” in the sense of “manmade” and what is “natural.” On the contrary, I think he avails himself of elements that characterise place, where nature is endowed with such untamed force as to consume all human artefact (in contrast to the opposite tendency, which is the case almost everywhere else in the world). This makes us feel that humankind and its products are wholly at one with nature. I refer not just to those images in which the human legacy is merely a vestige of the past and is fated to slowly disappear (Fagranes, Skinnalon, Rif, Heiðarhöfn, Assel), but also to those in which human presence is still actively making an impact (Fontur, Tungusel, Svalbarð, From Steinholt). Yet, it is a presence that takes account of, and is determined by, the context in which it is placed, thus showing a respect that I am sure the photographer admires and shares. Indeed, his is truly the wrenching, nostalgic hymn of one who considers a respectful exchange with the universe possible only when myriad human stratagems are unable to overcome the primordial power of nature itself.

Sky and Sea

The sea as Christopher photographs it makes us want to invent specific names for each of its individual “states,” just as when Inuit people employ various terms to refer to the snow in its many variations. There is a flat seascape bathed in a luminous ray of slightly clouded sunlight: It opens our hearts and conveys a sense of boundless serenity (Sölvanöv). Another image reveals a tongue of water sinuously or jaggedly sliding into coves set against a line of distant hills, with an overhanging sky so immense as to seem out of proportion with the rest of the scene (Langanes on the Horizon). Then there’s the sea darkened by a looming mass of clouds that appear so dangerously close to the photographer’s lens and the viewer as to spark the fear of being sucked up by its threatening force. A seagull hunting for fish hovers over an expanse of rough, leaden waves, conveying an unpleasant chill (Þistilfjörður). Then again, the sea is photographed from a slightly elevated position: the water is choppy, but not threatening, while separated from the sky amid hazy layers of steam and is cut by a curious line formed by merging currents (Sealine). The more I observe them, the more I realize that, despite constituting an objective, macroscopic reality, these seascapes embody the theme through which Christopher best expresses his state of mind, employing them as he sees fit and rendering them a docile, ductile conduit of himself.

The sky is just as immense and intense and it is sometimes contrasted with the expanse of land and sea in which it is mirrored (Naustinn, Sandkrokur, Near Haldorskot). At other times, it becomes the sole protagonist, sheared by the free or coordinated flight of birds (Arctic Terns, Geese) and is a symbol of an even greater, ineffable existence.

All the Rest

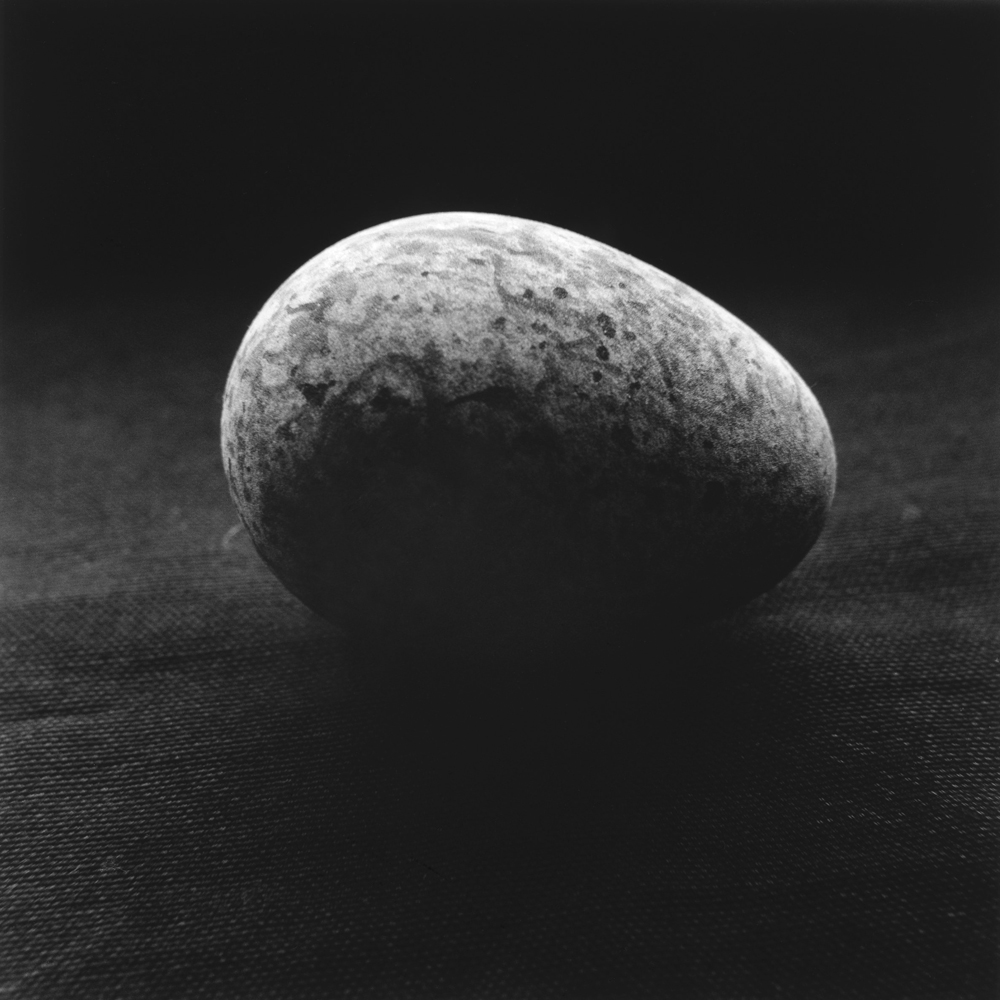

Beyond compositional harmony; the balance of light and dark areas; the interplay between straight, sharp lines and softly curved ones; and the thematic variety, there is one thing that strikes the viewer upon closer scrutiny of these photographs. Each image is the fruit of a single, fundamental quality: that of observing every aspect of the world with a careful, thoughtful, affectionate eye. In Christopher’s view, value is not attributed to something based on some hierarchical order: he captures the essence of each thing, person, animal, or landscape and considers it a living piece of the universe. There is no inferiority or superiority complex, and not even an equality complex (as the Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh suggests) because the boundaries between one thing and another disappear, making the mineral, animal, and vegetable kingdoms all part of a single symphony. A simple sledge lying in the snow, a frosted glass cake stand, an old dusty armchair, a guillemot’s egg—all of these shift us from the boundless realm of nature to the more intimate episodes of daily life, in which we may more sharply recognize the signs that mark the passage of time.

This is a notion that specifically distinguishes humankind and to which we perhaps owe our painful awareness of the finite. Christopher’s images and the timeless, suspended state they evoke help us to overcome that awareness, lifting us aloft towards vaster horizons.

Monica Dematté

© all images by Christopher Taylor / TASVEER Gallery / Mo Art Space / Galerie Camera Obscura // The publication will be available from: Kehrer Verlag

Segni nel tempo

Steinholt (o l’origine dei nomi) è la terza serie di immagini dedicata da Christopher Taylor all’Islanda, paese d’origine della moglie Álfheiður. La prima è denominata ‘Sotto il ghiacciaio’ (From under the glacier, 1996–1998) in omaggio al libro di Halldor Laxness „Christianity at Glacier“ (1972), mentre la seconda è stata scattata sulle isole Westman (Vestmannaeyjar, 2006–2010 ).

Il rapporto con la natura e la vita umana sul territorio islandese è andato approfondendosi da quando Christopher e Álfheiður. sono entrati in possesso di una modesta casa di famiglia chiamata Steinholt nel piccolo centro di Þórshöfn sulla costa nord occidentale del paese. Da allora Christopher ha trascorso tutte le estati nel minuscolo borgo marinaro, che ospita circa 300 persone, dedicandosi al restauro della casa, lavorando in una fabbrica di confezionamento del pesce e soprattutto esplorando il territorio circostante in lunghe e impegnative escursioni quando il tempo atmosferico lo permetteva. Non più ospite di passaggio colpito e affascinato dalla grandezza incontrastata della natura, o prigioniero di ambienti chiusi durante i giorni di cattivo tempo, Christopher condivide ora parte della sua vita con i compaesani di Þórshöfn e aggiunge senso al suo essere lì, rendendosi interprete dell’ambiente circostante e seguendo le tracce che tante vite ormai spente hanno lasciato nel paesaggio e nei ricordi di coloro che ci sono ancora.

Le storie che Christopher ha raccolto, sia per via orale che attingendo alle memorie collettive redatte da un maestro itinerante, Benjamin Sigvaldsson, lo hanno colpito e commosso per la semplicità e durezza che le caratterizza. Sono vicende di donne e uomini la cui unica occupazione e preoccupazione è stata di riuscire a sopravvivere in un ambiente severo e inospitale. Allevatori di poche pecore, pescatori quando il mare lo permetteva, agricoltori di piante sparute in un paese dove anche gli alberi crescono a stento per via del vento e del freddo, sono stati protagonisti a volte eroici di situazioni al limite. Quasi tutti costretti a lasciare le fattorie isolate dove sono nati perché non garantivano loro la sopravvivenza, hanno dovuto crearsi una vita altrove. Alcuni hanno subito soprusi, altri hanno dimostrato un animo generoso e fermo anche nelle peggiori difficoltà; tutti hanno vissuto faticosamente prendendo quel poco che potevano dall’ambiente. Nella serie di fotografie che Christopher ha riunito sotto il titolo di Steinholt – o ‘origine dei nomi’, alludendo al fatto che i nomi dei maggiori d’età vengono tramandati ai più giovani per prolungarne la memoria – il fotografo ha creato un suo affresco personale che, pur intendendo in alcuni casi evocare il passato in maniera anche puntuale, va oltre. Le sue immagini, anche quando ritraggono luoghi e vicende ben precise, non hanno bisogno di alcuna spiegazione aneddotica. La natura di quelle zone, così poco adatte alla vita umana, possiede una bellezza e una purezza difficile da trovare in luoghi più ospitali, mentre le residenze umane – si tratti di edifici ormai totalmente in rovina o abbandonati da poco – suppliscono alla povertà degli arredi con viste mozzafiato dalle finestre scardinate.

Nell’epoca del digitale e della comunicazione veloce e distratta, Christopher continua ad utilizzare macchine fotografiche analogiche, vecchie e pesanti, e rullini in bianco e nero che sviluppa e stampa personalmente. Ai mesi trascorsi nel paesaggio isolano, esposto al vento e alle intemperie, seguono lunghi giorni nella sua camera oscura nel sud della Francia, passati a rivedere e fissare le memorie su carta. Con il solo sollievo di una tazza di tè forte, il fotografo si auto-impone un lungo periodo di ‘buio’ dopo l’estate islandese di luce infinita. È attraverso questa dura disciplina che vengono distillate le immagini che ci arrivano, inni alla bellezza in cui il bianco e nero nelle infinite sfumature riescono a dare un senso più rarefatto e alto a quei riquadri di vita che Christopher ha colto.

Paesaggi, architetture o parti di esse, animali e ritratti: sono questi i temi di tutte e tre le serie dedicate all’Islanda, e ne restituiscono un quadro abbastanza completo. Nonostante in India Christopher si sia cimentato con grande successo a ritrarre le metropoli Kolkata e Mumbai, sono convinta che i suoi soggetti preferiti siano gli spazi aperti, naturali, dove l’occhio si spinge molto lontano o si concentra sul molto vicino, su particolari molto comuni che lui rende poetici e significativi (penso all’anatra che cova o al topo morto su una zolla) o su orizzonti infiniti che colpiscono e a volte fanno paura per la loro energia primordiale. Christopher ama la libertà, ama poter scomparire e non venir cercato né trovato, e il territorio islandese è in grado di accontentarlo. Quando una mattina esce di casa, dopo aver atteso per giorni che le condizioni meteorologiche si stabilizzino almeno un po‘, deciso a spingersi fino a Heljardalur (circa 50 km da Þórshöfn), la valle dell’inferno, dove si dice venissero portati a morire i vecchi, i malati e gli handicappati prima dell’inverno, sa di dover affrontare un percorso faticoso su terreno infido, senza sentieri e con punti di riferimento incerti. Sa che deve arrangiarsi da solo davanti a ogni imprevisto, e che il clima potrebbe portargli sorprese inaspettate da cui deve essere in grado di difendersi. Si mette insomma nelle condizioni più simili a quelle delle persone che fino a una cinquantina di anni fa vivevano in queste zone; anzi ancora più difficoltose in un certo senso, perché non è cresciuto lì.

Sguardi familiari

Rispetto alle fotografie scattate in Cina e in India, i due paesi più frequentati oltre all’Islanda, qui è la sua vita familiare e personale a venire coinvolta. È vero che l’interpretazione individuale forma sempre e comunque ogni immagine; gli scatti in questione però hanno qualcosa di più intimo, perché rievocano la storia della famiglia di Álfheiður. Christopher cerca nelle tracce del passato e nell’ambiente circostante una chiave che gli faccia comprendere meglio la compagna con cui ha trascorso più di trent’anni. In Islanda non è quindi un viaggiatore, seppure molto informato e attento, ma un uomo che vuole sentirsi parte di quello che vede e se ne vuole fare una ragione. La modalità con cui esprime questa appartenenza è però solo suggerita: i particolari autobiografici sono emblematici, e a mio parere non è importante se una delle fattorie crollate sia quella dove vivevano i progenitori della moglie, perché ogni islandese può trovare vicende analoghe nella storia della propria famiglia.

I ritratti sono di persone che, oltre ad abitare a Þórshöfn o dintorni, hanno (avuto) un rapporto con la famiglia di Álfheiður o con il fotografo stesso, che li ha incontrati durante la quotidianità o le escursioni e li ha riconosciuti come donne e uomini che incarnano l’essenza della gente del luogo. Sono uomini e donne con cui Christopher ha trascorso ore o giorni, con cui ha parlato e mangiato, che ha osservato per carpirne analogie e differenze. Si può dire che siano in posa, nel senso che sapevano di essere fotografati, ma i loro sguardi dimostrano che non si sono modificati a causa dell’obbiettivo. Mantengono una ‘integrità’ interna sostenuta dalla sensazione di essere in sintonia con l’immagine di se stessi veicolata dallo scatto del fotografo – indice di grande fiducia. Più degli altri soggetti (paesaggi, architetture) tendiamo qui a chiederci chi siano, ci immaginiamo aneddoti e parentele che spesso esistono ma credo che, come tutte le immagini di Christopher, anche questi ritratti vivano di vita propria e possano nutrirci anche solo di sguardi muti ma intensi. Forse l’unico ritratto veramente ‘costruito’, che merita una breve spiegazione, è quello della moglie che tiene in mano uno specchio appartenente alla nonna Álfheiður (da cui ha mutuato il nome); il volto appare però in parte, come per suggerire che la Álfheiður contemporanea si riconosce solo parzialmente nella figura dell’amata e rispettata nonna, perché la vita l’ha portata molto lontano, dove ha avuto possibilità inimmaginate e inimmaginabili.

Linee e aperture

Da quando seguo il lavoro di Christopher (sono ormai più di dieci anni) ho notato la sua predilezione per composizioni centrali, solide, preferibilmente di formato quadrato e spesso costruite su linee rette. Quest’ultima è una caratteristica più ovvia quando ritrae architetture, ma penso anche ad alcune nettissime linee d’orizzonte nelle numerose marine. La visione è quasi sempre simmetrica, e mira ad un’armonia che rende l’immagine perfettamente equilibrata. C’è una grande, innata capacità di calibrare gli elementi, per cui a uno spazio troppo ‘pieno’ o scuro fà da contrappunto un’area vuota o luminosa le cui dimensioni non sono necessariamente uguali, ma corrispondono esattamente a quanto serve per bilanciare visivamente l’immagine; a volte sono sprazzi di luce isolati, ma tanto potenti e significativi da costituire un contrappunto sufficiente anche ad estese aree di oscurità. In molte fotografie c’è un sapiente accostamento di linee rette e linee morbide, organiche, e a me pare che l’occhio di Christopher non intenda distinguere fra ‘artificiale’, nel senso di ‘costruito dall’uomo’, e ‘naturale’. Anzi, mi sembra che egli si avvalga delle caratteristiche di questi luoghi, dove la natura ha una forza talmente indomita da inghiottire gli artefatti umani (piuttosto del contrario, come accade in quasi ogni altro luogo al mondo) per farci sentire che anche il genere umano – e con esso i suoi prodotti – è a tutti gli effetti parte di essa, della natura. Non mi riferisco solo a immagini come quelle dove il retaggio umano non è che vestigia del passato ed è destinato a poco a poco a scomparire (Fagranes, Skinnalon, Rif, Heiðarhöfn, Assel), ma anche ad altre in cui la presenza umana è ancora presente e attiva (Fontur, Tungusel, Svalbarð, From Steinholt), perché è una presenza che tiene conto e viene determinata dall’ambiente in cui è calata, dimostrando un rispetto che, sono sicura, il fotografo ammira e condivide. Anzi, il suo è proprio il canto struggente e nostalgico di chi ritrova la possibilità di un dialogo rispettoso con l’universo solo laddove i mille artifici umani non riescono ad avere la meglio sulla forza primordiale della natura.

Mare e cielo

Il mare ritratto da Christopher mi fà venir voglia di inventargli nomi specifici per ogni ‘stato’, così come i popoli del nord utilizzano termini diversi per definire la neve nelle sue varie condizioni. C’è il mare piatto, percorso dalla scia luminosa di un sole appena velato da una nuvola leggera, che ci apre il cuore e ci comunica un’infinita serenità (Sölvanöv), c’è la lingua che si addentra sinuosa o frastagliata nelle insenature, a cui corrispondono linee di lontane colline, sovrastate da un cielo tanto immenso da apparire sproporzionato (Langanes all’orizzonte), c’è poi l’acqua del mare, incupita da un’incombente nuvolaglia minacciosa e così pericolosamente vicina all’obbiettivo del fotografo e all’osservatore, da farci temere di venirne risucchiati. C’è una distesa di onde mosse e plumbee su cui pesca un gabbiano, che ci comunica uno spiacevole senso di freddo (Þistilfjörður) e un mare visto da una posizione intermedia fra quella di chi sta sulla barca e quella a volo d’uccello: increspato ma non minaccioso, separato dal cielo in strati indistinti di vapori, percorso da una curiosa linea formata dall’incontro di correnti diverse (Sea line). Più le osservo e più mi rendo conto che le marine, pur essendo una realtà macroscopica e oggettiva, sono forse il tema con cui Christopher riesce meglio ad esprimere il suo stato d’animo, utilizzandole a suo piacimento, rendendole docili e duttili interpreti di se stesso.

Il cielo è altrettanto immenso e intenso, a volte contrappunto alla distesa d’acqua o di terra in cui si specchia (Naustinn, Sandkrokur, Vicino a Haldorskot, Il cammino verso Heljardalur), altre volte protagonista assoluto, solcato da voli liberi o coordinati (Ternes artiques a Rif, Volo d’oche) e simbolo di un’esistenza ancora più grande e ineffabile.

Tutto il resto

A ben guardare, c’è una cosa che colpisce al di là dell’armonia compositiva, dell’equilibrio di luci e ombre, dell’alternarsi di linee diritte e taglienti o morbidamente curve, della varietà dei temi, ed è che ciascuna immagine è il frutto di una qualità fondamentale: la capacità di guardare ogni aspetto del mondo con un occhio attento, consapevole, affettuoso. Non c’è una scala di valori nel sentire di Christopher: ogni cosa, persona, animale o paesaggio sono colti nella loro essenza, sono una tessera vivente dell’universo. Non esiste il complesso di inferiorità o di superiorità, e nemmeno quello di uguaglianza (come suggerisce il maestro buddista Thich Nhat Hanh), perché spariscono i confini fra una cosa e l’altra, fra i regni minerali, animali e vegetali, e tutto fà parte di un’unica sinfonia. Una semplice slitta nella neve, un piatto di vetro smerigliato per torte, una vecchia poltrona polverosa, un uovo di uria (guillamot), ci fanno passare dalla sconfinata dimensione naturale a episodi più intimi, quotidiani, in cui riconosciamo più evidenti i segni dello scorrimento del tempo.

Una nozione che è propria del genere umano e alla quale dobbiamo, forse, quel doloroso senso di finitezza. Le immagini di Christopher, con la loro sospensione sovratemporale, ci aiutano a superarla e a librarci in orizzonti più ampli.

Monica Dematté

© all images by Christopher Taylor / TASVEER Gallery / Mo Art Space / Galerie Camera Obscura // The publication will be available from: Kehrer Verlag