Thomas Ruff

Thomas, you are doing all the band photos now

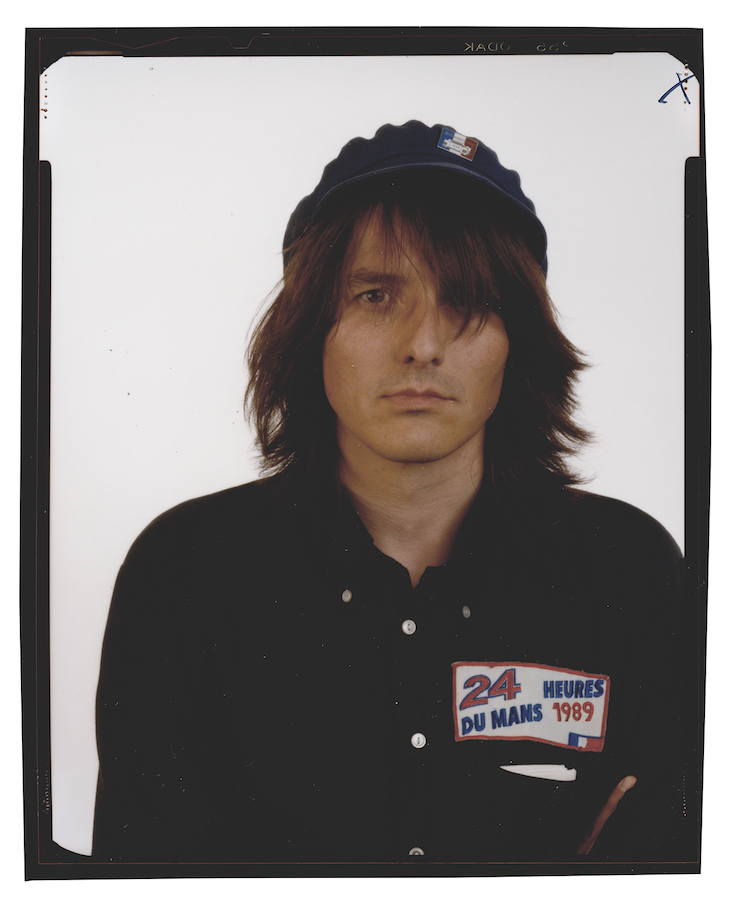

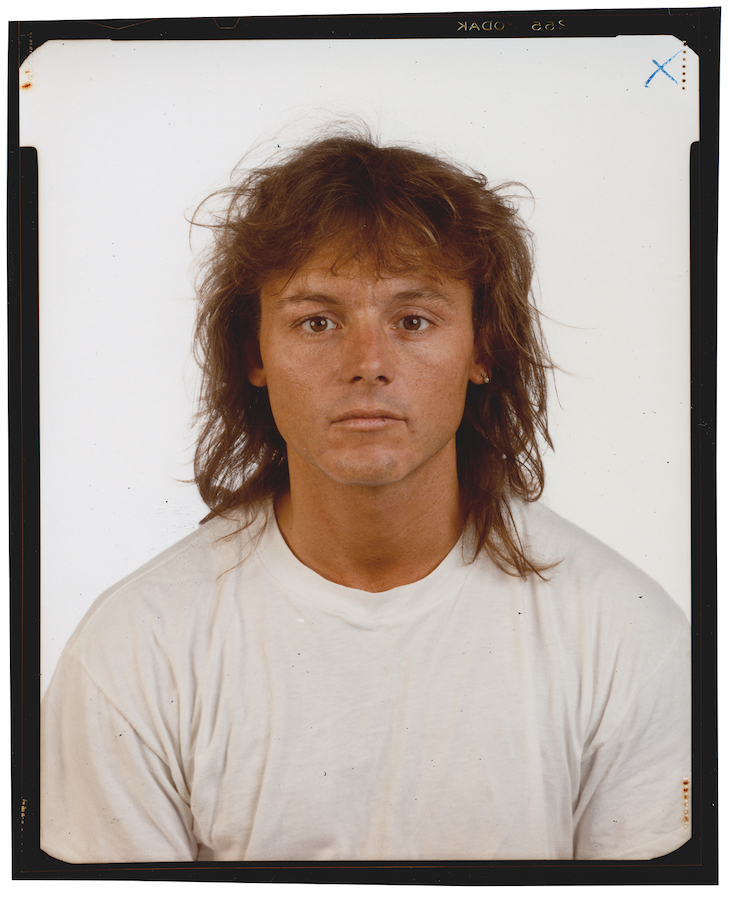

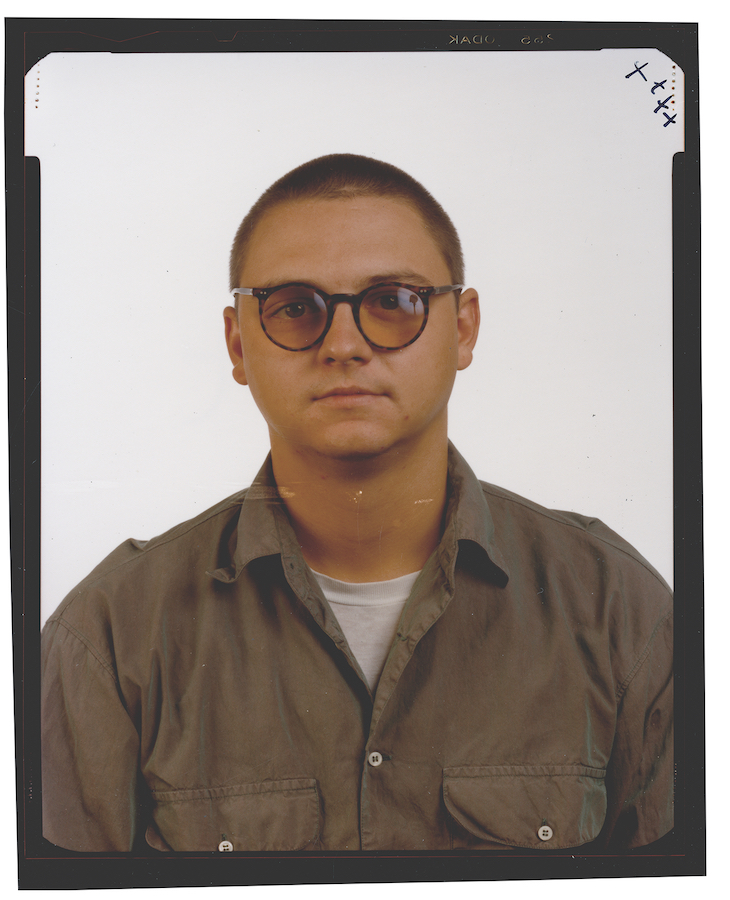

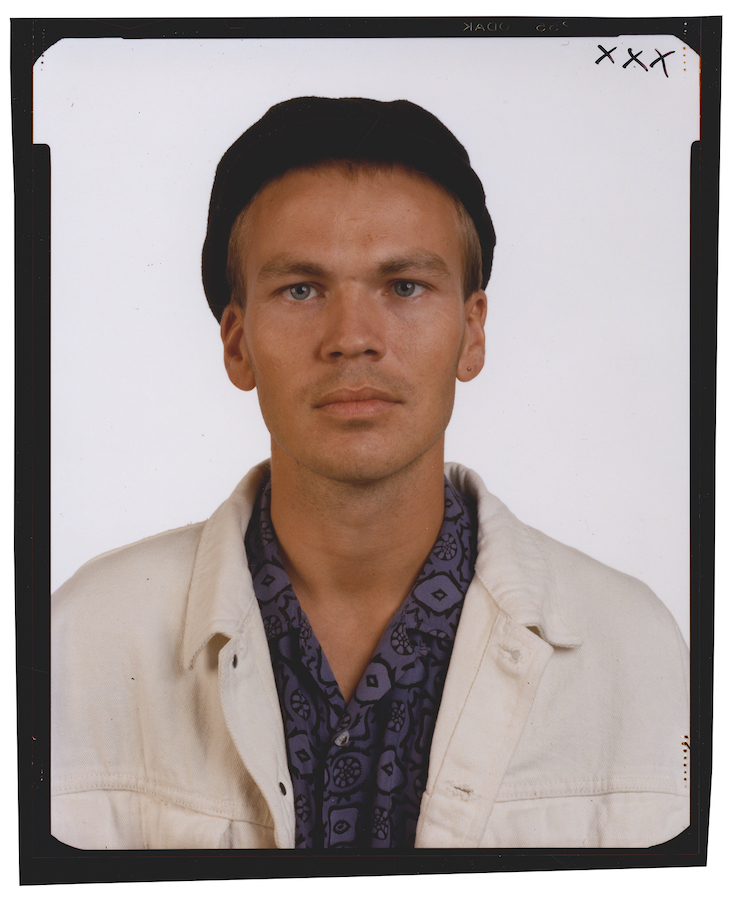

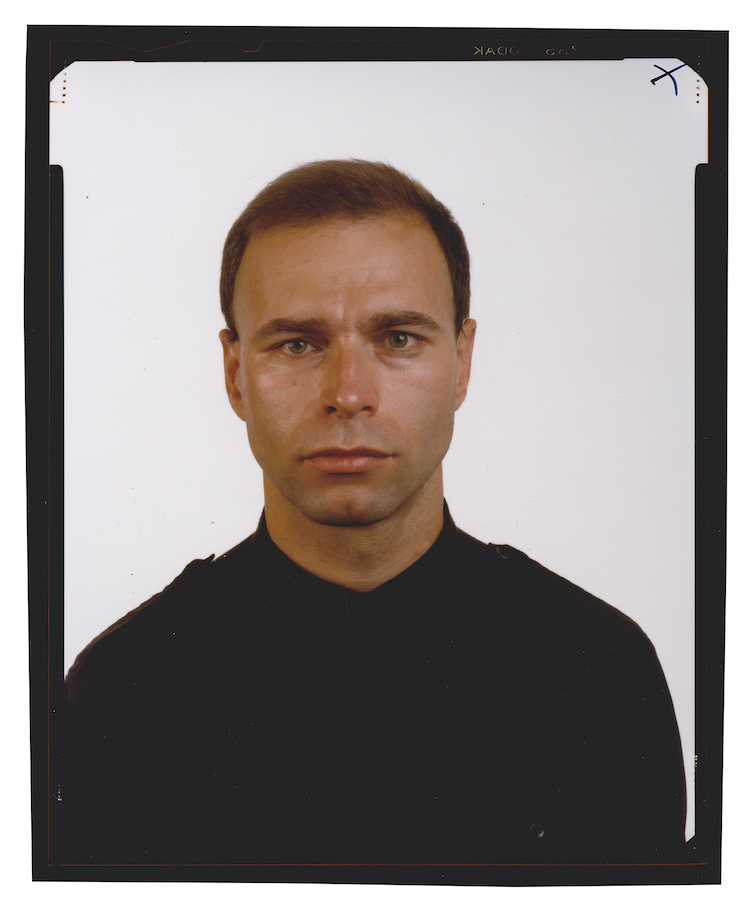

Thomas Ruff, who studied photography in the class of Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Kunstakademie Dusseldorf from 1977 to 1985, is regarded as a pioneer of conceptual photography. He became famous in the eighties with huge color portrait photos of his friends and fellow students from Dusseldorf. Hardly anyone knows, however, that the first images of this portrait series have a background in music, as he specifically staged his first portraits for a record cover. With conceptual thoroughness, Ruff went on to further explore the possibilities of his non-gestural portrait photography reminiscent of passport photos, and almost singlehandedly revolutionized the hitherto small-format world of photography by making a leap in format: He was the first photographic artist to use the Diasec process — previously used only in trade fair and advertising photography. In the Hyper! exhibition — and for the first time — Thomas Ruff goes back into the source code of his photography, exhibiting six small-format contact prints of portraits he made in 1989 for the cover of the album Das Blaue vom Himmel by the Dusseldorf band Family*5.

Max Dax: In the Hyper! exhibition you show a series of six musician portraits: the members of the Dusseldorf band Family*5. Would you like to explain how your portraits actually came into being?

Thomas Ruff: I was a student at the Academy of Arts in Dusseldorf. In 1980 I had the idea to make portraits, and for us students, the conceptual artists of Minimal Art were our heroes back then. That’s why I decided to do very minimalist portraits. I started in black and white, but then switched to color relatively quickly, because the photos I had done before were in color. I didn’t want to do commercial photography, and I didn’t want to do any of those flattering shots from the portrait studio that people liked. I wanted to make super-objective, matter-of-fact portraits. For this I used a plate camera with a large format negative, so everything is really nice and sharp and you don’t see any grain. I then bought a lens equivalent to the portrait lens, which was 300 mm for the 4 x 5-inch camera. But it was actually a lens that is used for material photography.

For architecture?

Yes, for still life, but also for technical photography. The lens was really super sharp. Then I set the light, which was a flash. Later there were also two lights for the portrait and another light for the background. First I asked my friends from the academy if they would sit for my portraits. The first ones were Ka, Shampoo, Sigi and Stoya, who had a punk band at that time, they called themselves EKG. At the time Stoya worked in the record shop run by Carmen Knoebel, so she was up to date musically. Because I had a camera and a darkroom at the academy, they said, “Thomas, you’re our art director. You’re doing all the band photos now.” In return, they always had time to sit for my portraits and to try something new. New light, just to try it. That’s how the first portraits were created. My original idea was actually to take a passport photo.

A passport photo using rocket technology. You were shooting canons at sparrows.

Yes, sure. The plate camera was definitely a mighty weapon. I really liked the portraits. I wanted to continue the series and asked other friends at the Academy of Arts if they wanted to sit for me, and finally the wider environment, in bars. Back then we were often at the Ratinger Hof, where I knew a lot of people, who I also asked.

An atlas of your friends?

Rather a kind of portrait gallery of my friends and acquaintances.

How strictly did you follow your own passport concept?

The first portraits I made frontally. Each exposure, that is, each sheet film, cost four marks at that time, and development also cost four marks. So every time I pressed the shutter release, I had just spent eight marks. That was a lot of money for a student. That’s why at the beginning I only took four shots: the frontal, slightly left, slightly right and sometimes also a profile.

To portray the face as neutrally as possible, a light gray background would probably have been the best.

I did actually consider that for a moment, but it would quickly get boring in a series. That’s why I got myself some photo cardstock in different colors and laid them out on the table to be selected by the person who was to be portrayed. Somehow they always picked the right color for themselves. At that time there was the Fernsehwoche, a weekly television magazine, and on the cover there was always a portrait of an actor. Of course, it was always a grinning portrait, a friendly portrait. Every week, the color of the background changed. I liked that. I planned a series of one hundred portraits, exhibited in rows or in double rows, which would then be a sort of portrait gallery of my contemporaries — mixing the background colors as well as the different positions and head positions.

The asymmetry then revealed a symmetry through the hanging.

Exactly. And in addition, I always showed portraits in the same format: 24 x 18 cm. But more importantly, I distrusted conventional portrait photography. There is the history of the portrait in photography: there is Yousuf Karsh who worked with light to turn the head of Ernest Hemingway or Yehudi Menuhin into genius. For me, that kind of photography was totally suspect. I assumed that photography could not look even one millimeter beneath the skin. I thought that kind of personality-interpretive photography was false. That’s why I chose the passport mode.

Then in the eighties came the size jump. The large format was suddenly available. Then you increased the dimensions to 210 x 165 cm.

In Dusseldorf there was a demand in the fields of advertising and trade fair construction to produce large photos. And when such need arises, Kodak produces accordingly. So, all of a sudden, technology was available to me that artists had not used before. I immediately took advantage of that new technology.

That was easily possible with your large format negatives.

Exactly, it was a stroke of luck that I had previously used the large format negative and those portraits are therefore still sharp in very, very large format.

The portraits marked your artistic breakthrough. You became famous with them. Maybe that’s even how you transported photography into fine art.

The leap in format and this enormous success have something to do with each other. In 1985 I had an exhibition in a small gallery in Dusseldorf, where all the small portraits were shown on the wall. All of my friends who were in the pictures came to the opening, of course. Then someone said: “That’s Heinz!”, and pointed to the photo. And I said: “No, that’s the photo of Heinz. Heinz is over there.” In fact, it often happened that people confused photography with reality. They didn’t appreciate that they were standing in front of a photographic medium, but simply saw through the medium into reality. When I first showed the big portraits, no one said “that’s Heinz” anymore. But rather: “That’s a really big picture of Heinz.” That’s when they first understood that they were looking at a photograph. That was part of the success.

And in fact, no one had ever come up with the idea of assigning that kind of value to a passport photograph — even if it wasn’t one — and to give it that respect.

It’s probably also because the photographs were so large and so different from a painting or screen print or other artistic medium. People were really shocked by those pictures.

The big portraits also always had a white border, but no passe-partout.

When I started printing the portraits large, I really wanted to put them in a passe-partout, because for me a photograph belongs in a passepartout. At that time, however, there weren’t any passe-partouts in that size. So I thought about how to generate a white border that has a passe-partout character. That’s when my lab came to my aid and made cover films for me. These are films that are only transparent or black. So they built me a cover film with a window into which a portrait fits exactly, and the rest of the photo was then covered with black — so the exposed paper in the finished print was then white, and I had my big white border, my passe-partout.

You’d really have to explain that to people who work digitally today.

They don’t know about that anymore. They simply enlarge the surface area in Photoshop, put some white around it, and there you have it. We are living in the digital age now.

It was actually new to me that the beginnings of this series, in fact, were photos for a punk band you were friends with. You could use them as guinea pigs. What was your relationship with the members of Family*5?

Most of my friends back then, maybe sixty or seventy percent, were artists. Then there were a few other students who also frequented the Ratinger Hof, who I also portrayed. Then there were graphic designers, fashion designers — so it wasn’t just people from the Art Academy, but also many from the environment of the Ratinger Hof. And a couple of musicians were also there, including my friend Xao Seffcheque, whom I had previously portrayed. He had the band Family*5 and in 1989 he asked me if I could shoot six portraits for a cover. I still knew Peter Hein, also from the Hof, as lead singer of Fehlfarben, Mittagspause, Charley’s Girls and other bands. I didn’t know the other four, but that wasn’t a problem, because I’m curious about faces. And then it turned out that three of the six portraits actually fit perfectly in my series. That was a win-win situation — they had their LP cover and I had three new portraits.

All six portraits have a white background. Was that because you didn’t want to get too colorful on the album cover?

When I started to enlarge the portraits in 1986, I initially chose portraits with a colored background, but soon found that it was too much color. In the large format there is so much color in the face, in the clothes, in the hair, that this colored background was no longer necessary. In these giant formats, it also looks best if the person portrayed looks directly at the viewer. Almost all the portraits I made from 1986 had that large format, a white background and a frontal view looking into the camera. The presentation became a trademark.

For the exhibition you have chosen a very small form of presentation for the first time. We see contact sheets. While in 1986 you took the step into the gigantic, today in 2018, you go almost into the miniature. Why?

The exhibition is called Hyper! and it’s about music and art. You chose six portraits of Family*5 and not portraits by Thomas Ruff. That’s a difference. And that allows me to reveal the working process for the first time. Instead of processed final prints, we see the originals from the original source. We see the raw material. And we see three portraits that later joined the ranks of Ruff portraits, and three that were used only for the cover. In this context, I find that much more exciting than exhibiting established high-end prints.

You have an impressive Funktion One sound system in your studio that could probably blow the walls out from the inside. I assume you listen to music when you work.

I listen to music rather when I’m not working. I used to listen to a lot of music while working, actually for the entire day. But that has diminished over time. I have to answer the phone more often these days. For that reason, I usually listen to music when I’m not working or when I’m just looking at things.

What do you listen to for music?

Classical music, especially operas by Richard Wagner.

Are there any of Wagner’s operas that you would like to highlight?

Actually, I like to listen to all of his operas.

What is it that attracts you to the opera music of Richard Wagner?

Probably that murderous opulence — he really wants to kill people with his music.~

Interview: Max Dax

© Thomas Ruff, Family*5, Peter Hein, Rainer Mackenthun, Ferdinand Mackenthun, Martin Gräber, Markus Türk, Xao Seffcheque, jeweils 1989, Kontaktabzug vom 4 x 5 inch Negativ, chromogener Print, 59,5 x 49,5 cm / Courtesy of the artist // Deichtorhallen Hamburg, „HYPER! A JOURNEY INTO ART AND MUSIC“, curated by Max Dax / published with friendly permission by Deichtorhallen Hamburg, Max Dax and Thomas Ruff, 2019

Thomas, du machst jetzt die ganzen Bandfotos

Thomas Ruff, der in der Klasse von Bernd und Hilla Becher an der Kunstakademie Düsseldorf von 1977 bis 1985 Fotografie studierte, gilt als Pionier der Konzeptfotografie. Berühmt wurde er in den Achtzigerjahren mit riesigen, gestochen scharfen Farbportraitfotos seiner Freunde und Mitstudenten aus Düsseldorf. Kaum jemand weiß indes, dass die ersten Bilder dieser Portraitserie auf einen musikalischen Hintergrund verweisen, denn er inszenierte seine ersten Portraits konkret für ein Plattencover. Mit konzeptueller Gründlichkeit deklinierte Ruff im Anschluss die Möglichkeiten der gestenlosen, an Passbilder erinnernden Portraitfotografie weiter durch und revolutionierte mit dem Formatsprung quasi im Alleingang die bis dahin auf Kleinformate beschränkte Welt der Fotografie: Er benutzte als Erster die bis dahin nur im Messebau und in der Werbefotografie benutzte Technik des Diasec-Verfahrens auch in der Kunstfotografie. In der Hyper!-Ausstellung geht Thomas Ruff zum ersten Mal in den Quellcode seiner Fotografie und stellt sechs kleinformatige Kontaktabzüge von Portraits aus, die er 1989 für das Cover des Albums Das Blaue vom Himmel der Düsseldorfer Band Family*5 anfertigte.

Max Dax: In der Hyper!-Ausstellung zeigst du eine Serie von sechs Musikerportraits — die Mitglieder der Düsseldorfer Band Family*5. Magst du einmal erzählen, wie es überhaupt zu deinen Portraits kam?

Thomas Ruff: Ich war Student auf der Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. 1980 hatte ich die Idee, Portraits zu machen, und für uns Studenten waren damals die Konzeptkünstler der Minimal Art unsere Helden. Deshalb hatte ich mir vorgenommen, ganz minimalistische Portraits zu machen. Angefangen habe ich in Schwarz-Weiß, bin dann aber relativ schnell zu Farbe übergegangen, weil die Fotos, die ich davor gemacht habe, Farbe hatten. Ich wollte keine Werbefotografie machen, und ich wollte auch keine dieser geschönten Portraits aus dem Portraitstudio haben, auf denen sich die Leute gefallen. Ich wollte super-sachliche, objektive Portraits machen. Dazu habe ich dann eine Plattenkamera benutzt, also ein großformatiges Negativ, sodass alles wirklich schön scharf ist und man kein Korn sieht. Ich habe mir dann ein Objektiv gekauft, das der Portraitobjektivlänge entspricht, das waren 300 mm für die 4×5-Inch-Kamera. Das war aber eigentlich ein Objektiv, das für Sachfotografie benutzt wird.

Für Architektur?

Ja, für Stillleben, aber auch für technische Fotografie. Das Objektiv war wirklich superscharf. Dann habe ich das Licht gesetzt. Das war ein Blitzlicht, später waren es auch zwei Lichter für das Portrait und noch ein Licht für den Hintergrund. Ich habe dann als Erstes meine Freunde von der Akademie gefragt, ob sie mir Portrait sitzen könnten. Die ersten waren Ka, Shampoo, Sigi und Stoya, die hatten damals eine Punkband, die nannten sich EKG. Stoya arbeitete damals im Plattenladen von Carmen Knoebel und war dadurch musikalisch auf dem Laufenden. Weil ich einen Fotoapparat hatte und eine Dunkelkammer an der Akademie, haben die gesagt: „Thomas, du bist unser Art Director. Du machst jetzt die ganzen Bandfotos.“ Im Gegenzug hatten die dann immer Zeit, mir Portrait zu sitzen und dabei was Neues auszuprobieren. Neues Licht, eben zum Probieren. Da sind dann die ersten Portraits entstanden. Meine Idee war eigentlich, ein Passfoto zu machen.

Ein Passfoto mit Raketentechnik. Du hast mit Kanonen auf Spatzen geschossen.

Ja, klar. Die Plattenkamera war schon ein ganz ordentliches Geschoss. Die Portraits haben mir dann sehr gut gefallen, ich wollte die Serie dann weiterführen und habe weitere Freunde von der Kunstakademie gefragt, ob sie mir Portrait sitzen wollen, schließlich auch das weitere Umfeld, in Kneipen. Wir waren damals im Ratinger Hof, da kannte ich jede Menge Leute, die ich dann auch gefragt habe.

Einen Atlas deiner Freunde?

Eher eine Art Portraitgalerie meiner Freunde und Bekannten.

Wie streng bist du mit deinem eigenen Passbildbegriff umgegangen?

Das erste Portrait machte ich frontal. Jede Belichtung, also jeder Planfilm hat damals vier Mark gekostet, und die Entwicklung kostete auch vier Mark. Jedes Mal, wenn ich auf den Auslöser gedrückt hatte, war ich acht Mark los. Das war für einen Studenten viel Geld. Deshalb habe ich am Anfang wirklich nur vier Aufnahmen gemacht — die Frontale, leicht links, leicht rechts und manchmal außerdem noch ein Profil.

Um das Gesicht am neutralsten darzustellen, wäre vermutlich ein heller grauer Hintergrund am besten gewesen.

Das habe ich mir tatsächlich auch kurz überlegt, aber in Serie wäre das schnell langweilig geworden. Deshalb habe ich mir dann Fotokartons in verschiedenen Farben besorgt, habe die auf dem Tisch ausgelegt und den zu Portraitierenden auswählen lassen. Die haben dann irgendwie immer ihre richtige Farbe gepickt. Damals gab es eine Zeitschrift, die Fernsehwoche, auf deren Cover immer das Portrait eines Schauspielers war. Das war natürlich immer ein grinsendes Portrait, ein freundliches Portrait. Da wechselte jede Woche die Farbe des Hintergrunds. Das gefiel mir. Ich plante eine Anzahl von 100 Portraits, die dann in Reihe oder in Doppelreihe eine Art Portraitgalerie meiner Zeitgenossen werden sollte — bunt durchmischt mit den Hintergrundfarben wie auch mit den unterschiedlichen Positionen und Kopfhaltungen.

Die Asymmetrie ergab dann in der Hängung eine Symmetrie.

Genau. Und hinzu kam, dass ich die Portraits auch stets im selben Format, 24 x 18cm ausstellte. Viel wichtiger aber war, dass ich der herkömmlichen Portraitfotografie misstraute. Es gibt ja die Geschichte des Portraits in der Fotografie, und da gibt es einen Yousuf Karsh, der mit Licht gearbeitet hat, um den Kopf von Ernest Hemingway oder Yehudi Menuhin auf diese Weise eindeutig ins Geniehafte zu drehen. Diese Art von Fotografie war mir total suspekt. Ich bin davon ausgegangen, dass Fotografie keinen Millimeter unter die Haut schauen kann. Persönlichkeitsinterpretierende Fotografie fand ich verlogen. Deshalb der Passmodus.

Es gab dann in den Achtzigerjahren den Größensprung. Das große Format lag in der Luft. Die Portraits hast du dann auf 210 x 165 cm vergrößert.

Es gab in Düsseldorf Bedarf aus dem Bereich der Werbung und des Messebaus, große Fotos herzustellen. Und wenn der Bedarf da ist, produziert Kodak entsprechend. Insofern stand mir mit einem Mal eine Technologie zur Verfügung, die von Künstlern bis dato nicht verwendet worden war. Diese neue Technologie habe ich mir sofort zunutze gemacht.

Das war mit deinen Großformatnegativen ja problemlos möglich.

Genau, es war ein Glücksfall, dass ich zuvor bereits das großformatige Negativ benutzt hatte und diese Portraits daher auch im sehr, sehr großen Format noch scharf sind.

Die Portraits markierten deinen künstlerischen Durchbruch, mit ihnen bist du berühmt geworden. Vielleicht hast du damit sogar die Fotografie in die bildende Kunst überführt.

Der Formatsprung und dieser enorme Erfolg haben etwas miteinander zu tun. 1985 hatte ich eine Ausstellung in einer kleinen Galerie in Düsseldorf, da hingen die ganzen kleinen Portraits an der Wand. Zur Eröffnung sind natürlich auch all meine Freunde gekommen, die auf den Bildern waren. Dann sagt da jemand: „Das ist Heinz!“, und deutet auf das Foto. Und ich sage: „Nein, das ist das Foto von Heinz. Heinz steht da drüben.“ Es war tatsächlich oft so, dass die Leute die Fotografie mit der Wirklichkeit verwechselt haben. Die haben nicht gemerkt, dass sie vor einem fotografischen Medium stehen, sondern haben einfach durch das Medium gesehen, in die Wirklichkeit hinein. Als ich dann die ersten großen Portraits gezeigt habe, hat keiner mehr gesagt: „Das ist Heinz.“ Sondern: „Das ist aber ein großes Foto vom Heinz.“ Da haben sie zum ersten Mal geschnallt, dass sie ein Foto anschauen. Das war ein Teil des Erfolgs.

Es ist de facto auch niemand vor dir auf die Idee gekommen, dem Passbild, auch wenn es keines war, diese Achtung zu zollen, einen solchen Wert zu geben.

Wahrscheinlich liegt es auch daran, dass diese Fotografie so groß war und so anders aussah als eine Malerei oder ein Siebdruck oder ein anderes künstlerisches Medium. Die Leute waren regelrecht schockiert von diesen Bildern.

Die großen Portraits hatten stets auch einen weißen Rand — aber kein Passepartout.

Als ich die Portraits begonnen hatte groß abzuziehen, wollte ich die eigentlich zunächst ins Passepartout stecken, weil für mich eine Fotografie nun einmal ins Passepartout gehört. Damals gab es aber keine so großen Passepartouts. Also habe ich überlegt, wie man einen weißen Rand generieren könnte, der immerhin Passepartout-Charakter hat. Da kam mir mein Labor zur Hilfe und hat mir Strichdeckfilme gemacht. Das sind Filme, die nur transparent oder schwarz sind. Die haben mir also einen Strichdeckfilm mit einem Fenster gebaut, in den ein Portrait genau hineinpasst, und der Rest vom Foto wurde dann schwarz abgedeckt — im fertigen Abzug war das Papier dann weiß, und ich hatte meinen großen, weißen Rand, mein Passepartout.

Leuten, die heute digital arbeiten, muss man das ja regelrecht erklären.

Die kennen das gar nicht mehr. Die vergrößern im Photoshop einfach die Arbeitsfläche, geben rundherum Weiß dran, und dann war’s das.

Mir war tatsächlich neu, dass der Anfang dieser Serie Fotos für eine befreundete Punkband waren. Du konntest sie als Versuchskaninchen benutzen. Was war dein Verhältnis zu den Mitgliedern von Family*5?

Ein Großteil meiner Freunde, vielleicht 60 oder 70 Prozent, waren damals Künstler. Dann gab es aber auch ein paar andere Studenten, die ebenfalls im Ratinger Hof verkehrten, die habe ich auch portraitiert. Dann gab es Grafiker, Modemacher, Modemacherinnen — es waren also nicht nur Leute von der Kunstakademie, sondern auch viele aus dem Umfeld des Ratinger Hofes. Und ein paar Musiker waren ebenfalls dabei, darunter mein Freund Xao Seffcheque, den ich schon früher portraitiert hatte. Der hatte die Band Family*5 und fragte mich 1989, ob ich nicht sechs Portraits für das Cover schießen könnte. Peter Hein habe ich noch gekannt, auch aus dem Hof, als Leadsänger von Fehlfarben, Mittagspause, Charley’s Girls und anderen Bands. Die anderen vier hingegen kannte ich nicht, aber das war kein Problem, denn ich bin ja neugierig auf Gesichter. Und dann stellte es sich heraus, dass drei von den sechs Portraits tatsächlich perfekt in meine Serie passten. Das war dann eine Win-Win-Situation — die hatten ihr LP-Cover, und ich hatte drei neue Portraits.

Alle sechs Portraits haben einen weißen Hintergrund. Weil es auf dem Plattencover nicht zu bunt zugehen sollte?

Als ich 1986 angefangen habe die Portraits zu vergrößern, habe ich zunächst Portraits mit farbigem Hintergrund ausgewählt, fand dann aber bald, dass das zu viel Farbe war. In der Vergrößerung ist so viel Farbe im Gesicht, in der Kleidung, in den Haaren, dass dieser Farbhintergrund nicht mehr notwendig war. In diesen Riesenformaten sieht es zudem am besten aus, wenn der Portraitierte den Betrachter direkt anschaut. So gut wie alle Portraits, die ich ab 1986 gemacht habe, hatten dieses Großformat, einen weißen Hintergrund und den frontalen Blick in die Kamera.

Für die Ausstellung hast du erstmals eine ganz kleine Präsentationsform gewählt. Wir sehen Kontaktabzüge. Während du 1986 den Schritt ins Gigantische gegangen bist, gehst du heute, 2018, ins fast Miniaturhafte. Warum?

Die Ausstellung heißt Hyper! und es geht um Musik und Kunst. Du hast dir sechs Portraits von Family*5 ausgesucht und nicht Portraits von Thomas Ruff. Das ist ein Unterschied. Und das erlaubt es mir, erstmals diesen Arbeitsprozess offenzulegen. Wir sehen statt prozessierter finaler Abzüge die Originale von den Originalen. Wir sehen das Rohmaterial. Und wir sehen drei Portraits, die später in den Rang von Ruff-Portraits aufstiegen sowie drei, die nur für das Cover verwendet wurden. Das finde ich in diesem Kontext viel spannender als etablierte High-End-Abzüge auszustellen.

Du hast eine tolle Funktion-One-Anlage in deinem Atelier stehen, mit der du wahrscheinlich dein Studio von innen ausbeulen kannst. Ich schließe daraus, dass du Musik hörst, wenn du arbeitest.

Musik höre ich eher, wenn ich nicht arbeite. Früher habe ich beim Arbeiten sehr viel Musik gehört, eigentlich den ganzen Tag. Das hat dann aber mit der Zeit nachgelassen. Ich muss heute auch öfters ans Telefon gehen. Insofern höre ich Musik meistens, wenn ich nicht arbeite oder wenn ich nur noch Dinge anschaue.

Was hörst du dann für Musik?

Klassische Musik. Vor allem Opern von Richard Wagner.

Gibt es Wagner-Opern, die du besonders hervorheben würdest?

Eigentlich höre ich alle seine Opern gerne.

Was zieht dich an Wagner so an?

Wahrscheinlich diese mörderische Opulenz. Dass er wirklich die Leute mit seiner Musik umlegen will. ~

Interview: Max Dax

© Thomas Ruff, Family*5, Peter Hein, Rainer Mackenthun, Ferdinand Mackenthun, Martin Gräber, Markus Türk, Xao Seffcheque, jeweils 1989, Kontaktabzug vom 4 x 5 inch Negativ, chromogener Print, 59,5 x 49,5 cm / Courtesy of the artist // Deichtorhallen Hamburg „HYPER! A JOURNEY INTO ART AND MUSIC“, kuratiert von Max Dax / Online publiziert mit freundlicher Genehmigung der Deichtorhallen Hamburg, Max Dax und Thomas Ruff, 2019